Image Source: Mearth Live.

Update 4 : Feb. 14 2009, 07:12:00 UT

The first reports are coming in. Gregor Srdoc in Croatia got a lightcurve through most of the night for HD 80606 combined with HD 80607. No sign of a transit, but the data is relatively noisy due to imperfect weather.

Veli-Pekka Hentunen reports that weather conditions in Finland were bad generally, and were specifically bad in Varkaus.

At least four sets of observations from various locations in Arizona are currently underway, including both the 40” and the 1.3m at USNO Flagstaff under the able command of Paul Shankland.

Jonathan Irwin reports that data from Mearth through 5 UT shows no sign of an egress.

Ohio State Grad Student Jason Eastman reports on his remote Demonex observations (from the comments page):

Halfway through the night…

We started observing at UT 02:30 in the V band. No sign of an egress at the ~0.005 mag level.

http://www.astronomy.ohio-state.edu/~jdeast/demonex/HD80606b.R.2009-02-14.jpg

That link will be updated with the entire night’s data in the morning.

So it’s not looking particularly good for a transit, but I’m really happy that data is coming in. We’ll have a definitive answer sometime tomorrow.

Thanks to everyone who observed. It’s really cool how a planet 190 light years away can bring observers all over the globe into a common mission.

Update 3 : Feb. 13 2009, 23:29:00 UT

We’re now closing in on the moment of inferior conjunction, which hopefully will wind up being the midpoint of a central transit. The current weather in Europe looks like it’s clear for observers in Finland and Northern Italy, so it’s now quite likely that we’ll get a definitive answer from the campaign.

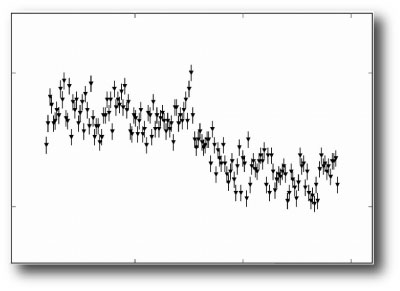

No word yet on whether an ingress was observed, but Jonathan Irwin did send a nice light curve from last night’s baseline run with Mearth. He writes:

Here’s our entire night of data (about 11 hours) from one telescope, using 80607 as the comparison star. Raw and binned x12 (about 5 minutes per bin). We are getting rms scatter of about 1.6 times Poisson with this fairly quick reduction.

There is usually a slight offset when the target crosses the meridian (data point 777) due to flat-fielding error, that I have not removed in this – over the ~20 arcsec separation of the pair it’s pretty small. There is also a bit of a blip there as my guide loop recovers its lock after crossing – still needs a little tuning :)

Fingers crossed for tonight!

Update: Clear Skies in Arizona. Dave Charbonneau writes:

http://mearth.sao.arizona.edu/live/

Clear skies. You can even watch the images in real time, and see how many

MEarth scopes are on ‘606…

Update 2 : Feb. 13 2009, 17:04:00 UT

It’s now the middle of the night in the Far East, and the transit window has opened. The weather in Japan looks a little spotty, but Southern China is in the clear.

Observers in Arizona reported good weather last night, but the forecast is a little iffy for tonight.

In addition, I just got an e-mail (UT 17:48) from Gregor Srdoc in Croatia, who is on the sky under quite good conditions just after nightfall…

Update 1 : Feb. 13 2009, 06:03:03 UT

There’s about a half-day left until the possible start of the ingress. On the map above, I’ve marked the locations of confirmed observers with small red dots. HD 80606b is 190 light years above the spot labeled with the orange circle.

Observers in the US are currently taking data of both HD 80606 and its binary companion, HD 80607. It’s always good to have an out-of-transit baseline photometric time series.

Dave Charbonneau checked in with a status report:

MEarth is ready. You can watch us in real time at

http://mearth.sao.arizona.edu/live/

If the roof is closed, it is cloudy.

The up-to-the-minute stop-action animations showing the disconcertingly reptilian movements of the telescopes are completely mesmerizing. Mearth (pronounced “mirth”) is located at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory on Mt. Hopkins in Arizona, and spends most of its nights searching for potentially habitable terrestrial planets transiting nearby M dwarfs. The telescopes have a list of ~2000 nearby red dwarf stars. Each star is subjected to repeated visits of ~30-45 minute duration. The idea is to catch transiting planets in progress and to broadcast the information to larger telescopes that can obtain immediate real-time photometric confirmation of a discovery. (For a more detailed overview of Mearth, see Irwin, Charbonneau, Nutzmann & Falco 2008.)

Update 0 : Feb. 12 2009, 22:47:40 UT

I’ll be posting updates on the global HD 80606b transit campaign as I get them, with newer updates going to the top of this post.

A number of observers have indicated that they’ll be on the sky. Right now, it looks like telescopes are confirmed for Finland, Israel, Italy, Japan and the US. Given the vagaries of the weather, however, it would be great if we can get as much coverage as possible. As Vince Lombardi would have put it, “We’re looking at 15%, so if you can get 1%, get out there and give 110%!”

Everyone is encouraged to comment as the campaign progresses (click the number next to the post title to access the discussion page). I’ve lifted the restriction that only allows registered oklo users to comment, but all comments are now held for moderation, in order to keep the Viagra contingent off the air.