HD 80606 b is one crazy place. With an orbital eccentricity of e=0.932, its orbit resembles a ball tossed almost straight up with a 111.4 day hang time. I’ve heard that in many European countries, periastron passage (when HD 80606 b whips through its closest approach) is known as ‘606 day, and is celebrated by a day off work filled with drunken and disorderly parades. I’m trying to bring the tradition over to the United States.

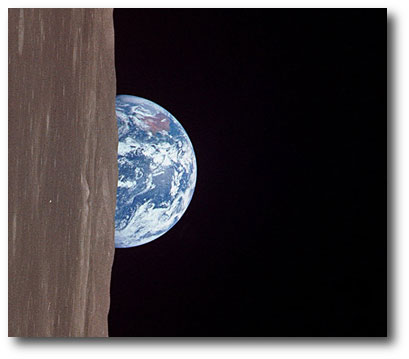

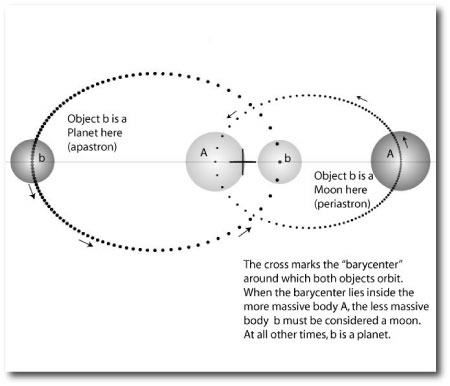

Today (as viewed from Earth) HD 80606 b is just starting to pick up speed on its inward plunge to the next ‘606 day, which occurs on August 31, 2006. The planet has spent the June and July cooling off near the far point of its orbit, at a distance of about 0.85 AU from the central star. It’s possible that weather in the upper atmospheric layers of the planet has spawned a street of category 10 hurricanes that will tear unimpeded around the planet until the steadily mounting insolation turns the driving rains into steam. During the month of August, the planet will fall in almost the full distance to the star, eventually swooping within 6 stellar radii as it whips through periastron.

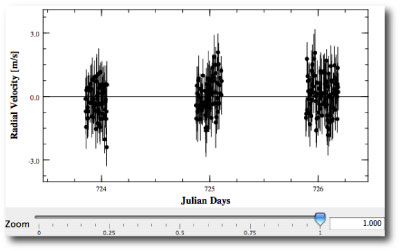

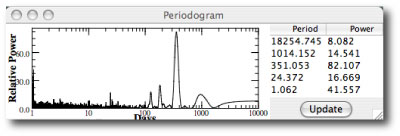

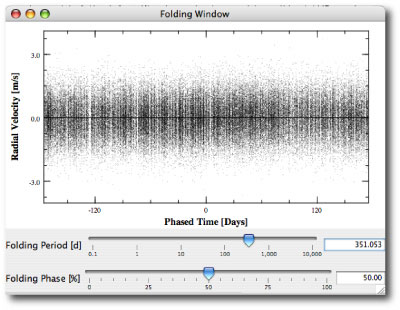

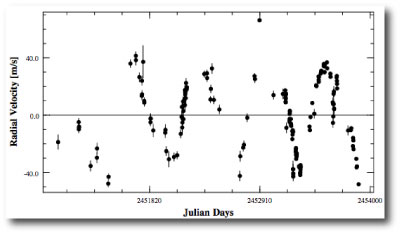

The discovery of the planet and its orbital solution were announced by the Geneva Observatory Planet Search Team in an April 04, 2001 ESO press release, and the radial velocities are available on both the downloadable systemic console and at the CDS repository (see Naef ef al 2001). The recent catalog paper by Butler et al. (see exoplanets.org) tabulates an additional set of 46 high quality velocities for HD 80606. Using the console to get a joint fit to the two datasets gives an updated set of orbital elements: P=111.4298 days, M=3.76 Jupiter masses, and e=0.9321.

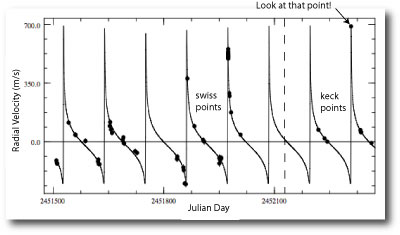

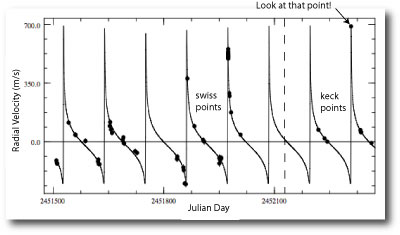

Several years ago, when the California-Carnegie radial velocities for HD 80606 started coming in, Geoff let me have an advance look at them. When I synched the new Keck points up against the Swiss points (which I’d extracted from a published postscript figure) I noticed something interesting. The Keck point obtained on Feb. 2, 2002 was more than 100 m/s above a cluster of Swiss velocities that had been obtained very close to periastron passage.

I got excited. The Keck observation suggested that the magnitude of the periastron swing is larger than had been estimated by the published fit. This in turn suggested that the eccentricity of the planet was even larger than the published value of e~0.93. I did an orbital fit and uncertainty analysis on the combined dataset. The best-fit eccentricity came out at a whopping e=0.971 +/- 0.018. An eccentricity this high implied that the planet was regularly swooping to within 2.5 stellar radii of the star. In order for this to be possible, the so-called tidal Q for the planet would have to be very high — higher than the value of around a million that had been inferred from the orbital circularization radii for the hot Jupiters.

In order to confirm the high eccentricity, it would be necessary to obtain more radial velocity measurements in the vicinity of the periastron swing. In June of 2004, I calculated a list of the upcoming periastron dates, and found that one was scheduled for July 11th, 2004 (UT), just a few weeks away. I looked at the schedule for the Keck I telescope, and saw that the California Carnegie team had been assigned a run covering July 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th. Then I checked where HD 80606 would be located in the Mauna Kea sky. The star was setting rapidly, and was already fairly far to the west at sunset, with and hour angle of more than five hours, and airmass of about three.

I wrote to Geoff and told him about the combined fit that suggested a high eccentricity. Would the star be high enough above the horizon for Keck to observe? He wrote back right away. He was also computing a high value for the eccentricity, and yes, it would be within the limits of observability if the telescope operator was notified in advance.

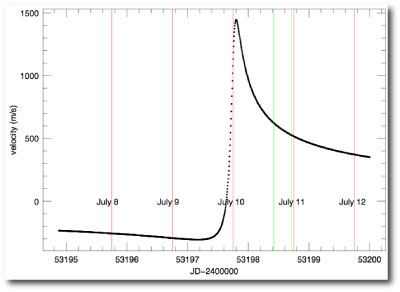

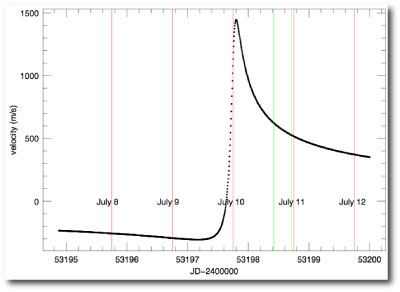

In the plot just above, I’ve reproduced the predicted radial velocity curve during the course of the run. The four vertical red lines show 8:00 PM Keck time on July 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th, 2004. Amazingly, the fit suggested that during the brief window of observability on July 10th local time (July 11th UT), the star would be smack in the midst of its most rapid acceleration! The radial velocity fit suggested that a standard six-minute exposure started at 07:30 PM on July 10th would span a reflex velocity change of 60 m/s. By contrast, it takes Jupiter 6 years to indude a 12 m/s velocity change in the Sun.

I waited impatiently through the run, eager to learn what the velocities would be. I kept my fingers crossed that the eccentricity would hold up at e=0.97. Money in the bank. Even if the velocities drove the eccentricity down to its 1-sigma low bound, to e=0.953, it would still be an exciting result, with potentially important consequences for the internal structure of the planet.

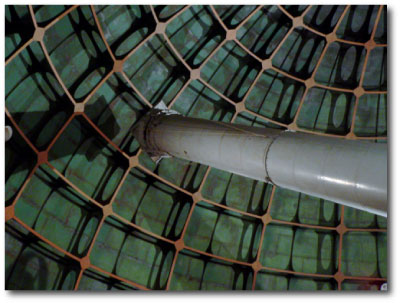

On July 10th, at 11 pm PDT (8 pm Hawaii time) I sat at my kitchen table, and imagined the scene on Mauna Kea, with the great dome open to the sky, and Keck I leaning practically on its side, straining to catch the rays of a distant star fading into the last moments of twilight. I thought of the planet itself, stellar furnace filling half the sky, literally jerking the star back into space as it screamed through periastron.

On the morning of the 13th, Geoff sent an e-mail with the velocities. The new fit gave e=0.945. I was stunned. What the @#%? I looked at the velocities themselves, On the 10th, on what was supposed to have been big night, the velocity had failed to rise at all from the value on the 9th. On the 11th, the velocity was only somewhat higher. It was clear that the big swing had occurred several hours afterward. On the 12th, the velocity was high, and clearly past the peak. The planet had arrived at periastron slightly more than a full day later than predicted.

The measured eccentricity was 2-sigma low, an occurrence that one expects less than 2.5% of the time. By chance, the high Keck velocity on Feb. 2, 2002 randomly came within one part in 2000 of arriving exactly at the radial velocity maximum. The fitting program interpreted this high point as suggesting a higher eccentricity than the planet actually has.

I was depressed for the next fifteen minutes. As usual, 95 to 97% of the “cool” discoveries that one turns up in the course of scientific life turn out to be spurious. You have to keep throwing your hat into the ring.

.

.