[A continuation of posts 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 on the formation of Jovian planets.]

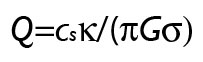

Phoebe (photographed by Cassini). The cores of the giant planets were built from millions of these objects.

In the primitive solar system, ice formed at the expense of water vapor wherever the temperature was lower than 150 degrees above absolute zero. The 150 K isotherm in the disk was located roughly at Jupiter’s current distance from the Sun, and is known colloquially as the “snowlineâ€. Just beyond the snowline, the planetesimals achieved their greatest ability to rapidly build themselves into larger bodies. It was cold enough for ice to be stable, yet close enough for the overall density of the disk to be high, and the planetesimals were prone to frequent collisions.

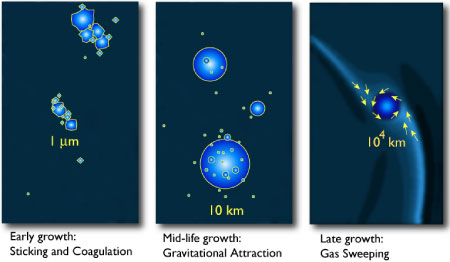

Low-speed planetesimals collisions were sticky events that can be simulated to wonderful effect with fast desktop computers. Imagine two Michelin Men, each loosely glued together, heading toward each other in a headlong embrace. A spare tire or two is lost in the collision, but one remains with a jumbled, combined mess. The first planetesimal collisions that seeded Jupiter’s core looked something like that.

Thousands of years passed, punctuated by these (initially) slow-motion catastrophes. The planetesimals gradually become fewer in number and individually larger. Those that experienced a few extra collisions in the beginning were able to take advantage of their burgeoning self-gravity to collide more often, and were thus able to grow faster (sound familiar?) Inevitably, a few big winners, called oligarchs, began to emerge. These oligarchs, with radii thousands of miles across, were massive enough to simply haul in their neighboring small-fry kilometer-sized brethren. The more an oligarch gets, the more it wants, and the farther its reach. A runaway occurs. Somewhere in the current vicinity of Jupiter, 4.54 billion years ago, an oligarch reached an Earth mass.

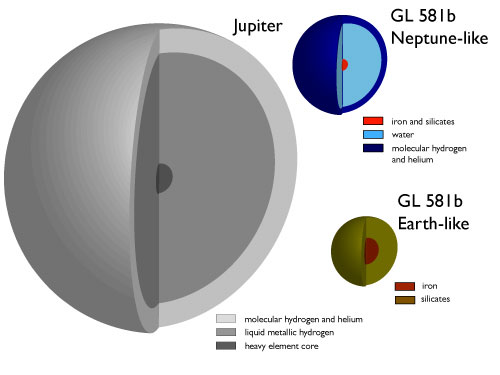

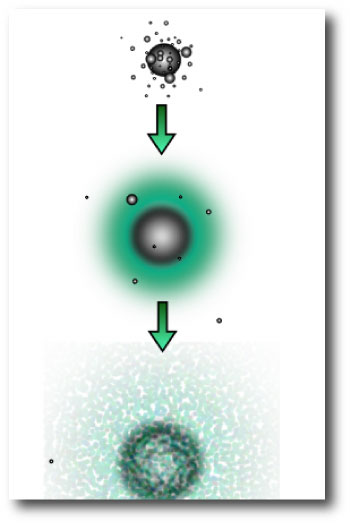

What would this oligarch have been like? Certainly, it would be something that we would have little difficulty calling a planet in distress. All riled up. A five hundred mile wide core of molten iron, surrounded by perhaps a thousand miles of pressurized plastic rock, not unlike the mantle of the Earth. Above that, thousands upon thousands of miles of hot, pressurized, water ocean. Floating atop the ocean, a tarry layer of hydrocarbons, perhaps with a smell like hot asphalt, and with an indistinct surface merging into a choking thick noxious atmosphere.

The atmosphere bulks up fast. Liberated hydrogen and helium gas bubbles up from the layers of denser materials in the interior. The oligarch passes several Earth masses in size, and grows massive enough to grab gas directly from the disk. Meanwhile, new planetesimals are arriving all the time. Kilometer-sized projectiles streak through the exosphere, exploding as they slam into the atmosphere. The unsettled skies are continuously ablaze with meteors. The temperature rises, becoming so warm that the atmosphere glows a dull coal-red in the darkness of the nebula.

When the growing oligarch, now a full-fledged protoplanet, reaches seven or ten times the mass of the Earth, it is pulling in gas as fast as it can. The atmosphere has swelled and bloated to a thickness of literally hundreds of thousands of kilometers. The gas glows fire-engine orange, and pours infrared light out into space. This radiation is accompanied by slow settling of the lower layers, providing room at the top for more gas to flow in.

Finally, the growth experiences its first taste of a slowdown. The consumption of rocky icy planetesimals has been so rapid that the total reservoir of these objects in the annular region of the nebula occupied by the planet is depleted. The planet has managed to effectively clear out the solid material from a vast ring-like region of the nebula. The region around the protoplanet still contains vast quantities of gas, but this gas is prevented from accreting onto the bloated planet. The planet can only add new gas as fast as the older gas is able to settle, and the gas can only settle by radiating and cooling.

For the next million years, the planet grows slowly. Gas flows in from the disk as fast as the cooling of the planet will allow, and as the mass of the planet increases, the annular ring of the disk from which planetesimals can be drawn also slowly increases in size…