Pythagoreorum quaestionum gravitationalium de tribus corporibus nulla sit recurrens solutio, cuius rei demonstrationem mirabilem inveniri posset. Hanc blogis exiguitas non caperet.

Listening in

As with everyone else, LIGO made my day.

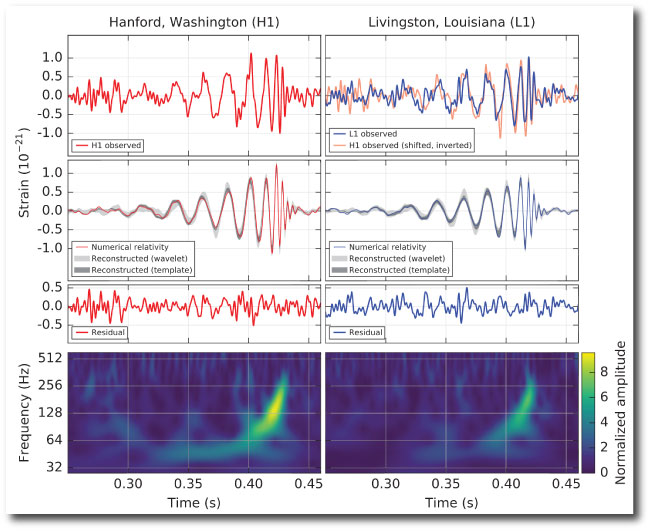

It’s interesting that transverse waves of spatial strain — ripples in spacetime — are consistently described as “sounds” in the media presentations. For example, the APS commentary accompanying the Physical Review Letter on GW150914 is entitled The First Sounds of Merging Black Holes.

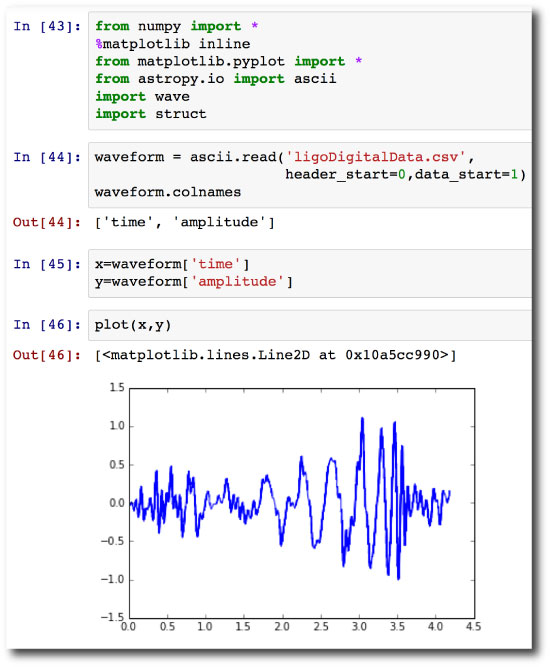

Quite frankly, Python is a threat to the scientific guild. What used to require esoteric numerical skills — typing in recipes in Fortran and stitching them together, or licensed packages, “seats”, always priced to keep the riff-raff out, now comes completely for free with a one-click install of an Anaconda distribution. All this stuff places anyone just a few lines away from hearing the sound on Figure 1, which APS posted as a teaser while they scrambled to get servers on line to handle the crush of download demand:

Here’s what I did this morning to “hear” the signal while waiting for the servers to free up, so that I could download the full paper.

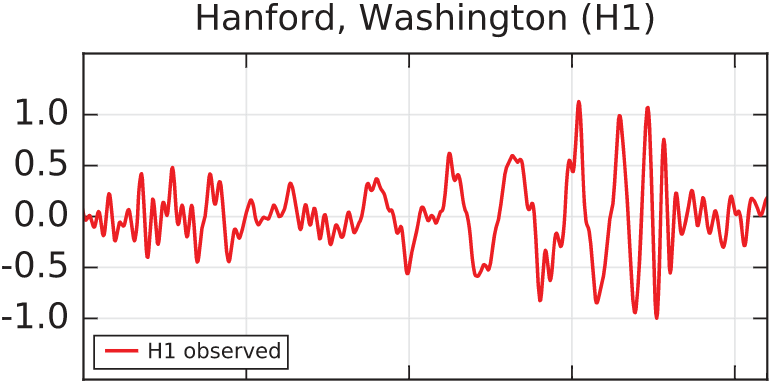

(1) Take a screen shot of the Hanford signal:

(2) Upload the screenshot to WebPlotDigitizer, and follow the directions to sample the waveform. After a bit of fooling around with the settings, the web app gave me a .csv file that I named ligoDigitalData.csv. It contains containing 1712 x-y samples of the waveform. I added a header line listing “time” as the first column, and “amplitude” as the second column.

(3) Fire up an iPython notebook, import a few packages, import the file, and check that it looks right:

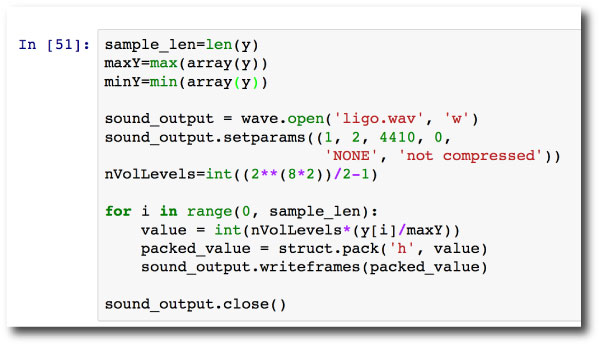

(4) The “wave” package packs integer samples into a .wav format file. A plain vanilla implementation at 4.41 kHz 16 bit sampling looks like this. Not exactly audiophile quality, but so cool nonetheless:

This produces a .wav file:

Now of course, one shouldn’t expect that a waveform that you can silkscreen onto a T-shirt is going to sound like the THX Deep Note…

And how ’bout them prediction markets? Over at Metaculus, the consensus among 99 predictors was that there was a 68% chance that the Advanced LIGO Team would publicly announce a 5-sigma (or equivalent) discovery of astrophysical gravitational waves by March 31, 2016. According to the Phys Rev Letter, the significance of the GW150914 detection is 5.1 sigma, so just over the bar. The question is now closed, and some users are going to be racking up some points.

If you missed out, there’s plenty more markets to try your hand at. New boson at the LHC anyone?

June 25, 2522

I remember the eclipse of February 26th, 1979 very clearly. In Urbana, Illinois, the moon covered 80% of the solar disk. It was a clear sunny day, and the crescent Sun projected magically through a pinhole into the 6th grade classroom.

Later, looking at a map, we noticed with considerable pride that a total eclipse will track over Southern Illinois on August 21, 2017. The date had an unreal, distant, science fiction feel to it.

Anthony recently posted a question on Metaculus that’s provocative, slightly creepy, and seems designed to transcend the day-to-day:

Will there be a total solar eclipse on June 25, 2522?

created by Anthony on Jan 28 2016

According to NASA, the next total solar eclipse over the U.S. will be August 14, 2017. It will cut right through the center of the country, in a swathe from South Carolina to Oregon.

A little over 500 years later, on June 25, 2522, there is predicted to be a nice long (longest of that century) solar eclipse that will pass over Africa.

In terms of astronomy, the 2522 eclipse prediction is nearly as secure at the 2017 one: the primary uncertainty is the exact timing of the eclipse, and stems from uncertainties in the rate of change of Earth’s rotation – but this uncertainty should be of order minutes only.

However, 500 years is a long time for a technological civilization, and if ours survives on this timescale, it could engineer the solar system in various ways and potentially invalidate the assumptions of this prediction. With that in mind:

Will there be a total solar eclipse on June 25, 2522?

For the question to resolve positively, the calendar system used in evaluating the resolution must match the Gregorian calendar system used in the eclipse predictions; the eclipse must be of Sol by a Moon with at least 95% of its original structure by volume unaltered, and must be observable from Earth’s surface, with “Earth” defined by our current Earth with at least 95% of its original structure by volume altered only by natural processes.

What do you think? Head over to Metaculus and make your prediction count.

“That star is not on the map!”

Yet its presence has been felt, trembling on the far-reaching lines of analysis.

Readers of Systemic certainly need no introduction to what I’m talking about.

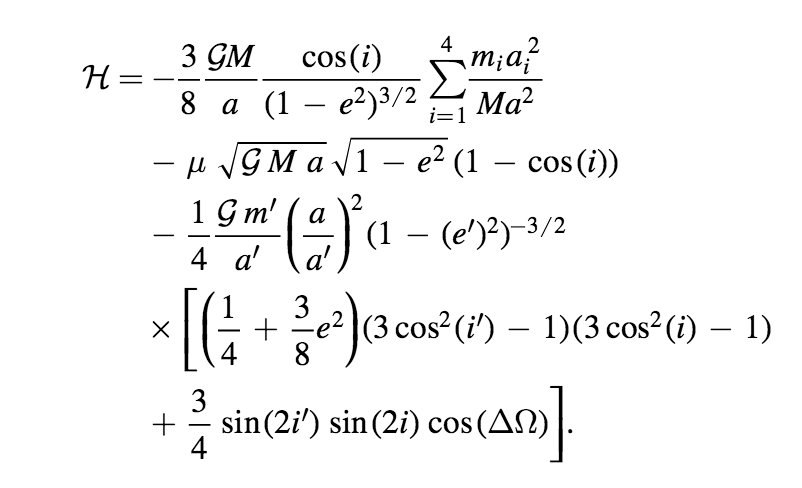

According to the Astronomical Journal’s website, Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown’s paper has been downloaded a staggering 243,547 times in the past five days. To the best of my knowledge, this is perhaps the only time that an autonomous Hamiltonian derived by transferring to a frame co-precessing with the apsidal line of a perturbing object, and then clarified by a canonical change of variables arising from a type-2 generating function, has garnered download numbers that beat out Adele, Justin Bieber, and Flo Rida’s latest figures,

As for the planet itself? A frigid as-yet unseen world with ten times the mass of Earth. Its twenty thousand year orbit is eccentric, and at aphelion it languishes with 500 m/s speed, drifting slowly against the spray of background stars. Its cloud tops glow in the far infrared, a mere 40 Kelvin above absolute zero. At the far point of its orbit, it is invisible to WISE in all its incarnations, and far fainter than the 2MASS limits. Obscure. In the optical, it reflects million-fold diminished rays of the distant Sun to shine in the twenty fourth magnitude. Dim, indeed, but not impossibly dim… Traces of its presence might already reside on the tapes, in the RAID arrays, suspended in the exabyte seas, if one knows just where and how to look.

And there is an undeniable urgency. In England, in 1846, following the announcement of Neptune’s discovery, and with the glory flowing to Urbain J. J. Le Verrier in particular, and to France in general, the Rev. James Challis and the Astronomer Royal George Airy were denounced for their failures in following up John Couch Adams’ predictions.

Adams had done essentially the same work as LeVerrier, but he didn’t push very hard to get his planet detected. The Cambridge astronomers marshaled only vague half-hearted searches, even though they had a substantially longer lead time than the astronomers at the Berlin Observatory who first spotted the planet. “Oh! curse their narcotic Souls!” wrote Adam Sedgwick, professor of geology at Trinity College in reference to Challis and Airy.

So what will it take to find Planet Nine? Mike and Konstantin have started a website that gives details and updates on the search.

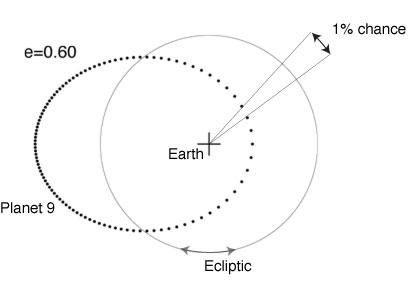

One point that’s interesting to remember is that while an eccentricity, e=0.6 is high, much higher than the rest of the planets in the solar system, it’s not all that high. This planet is no HD 80606b. While it’s true that it tends to congregate near the far point of its orbit, there’s a non-negligible chance of finding it anywhere on its trajectory. In the figure below, the planet is plotted at 100 equal-time increments along its orbit, which shows the distribution of probability for each segment of a great circle that rings the sky:

Similarly, if we assume that its radius is 75% that of Neptune, and that it has a similar albedo, its V magnitude will vary in the following manner during the course of its orbit:

I’ve got a sense — an irresponsible atavistic premonition, actually — that the planet will be caught just as it passes through the 700 AU circle.

We’ve set up a prediction market on the prospects for near-term discovery of Planet Nine at Metaculus. Sign up (or log in) and make your prediction count!

autoregression

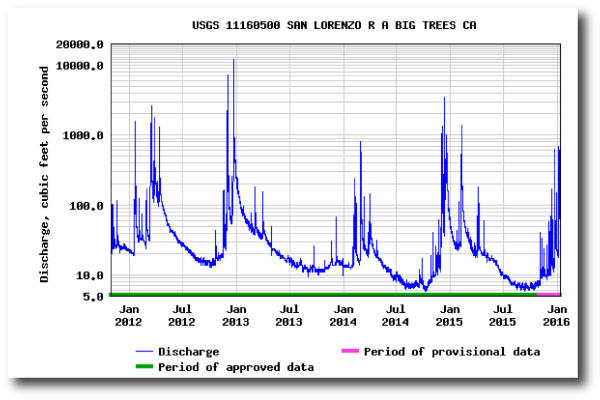

And in California, for the past several years, it mostly hasn’t. This summer, the creeks in the Santa Cruz Mountains were reduced to slight trickles, which was sufficiently alarming to cause me to start watching the USGS’s real-time web-based flow monitor for the San Lorenzo River. The growing drought is evident in the nadirs of this plot of the streamflow for the past four years:

This summer and last, the mighty San Lorenzo was scraping by at about five cubic feet per second, which was thousands of times less than the peak flow at the end of 2012. Stream flow depends on a number of known factors — watershed characteristics, rainfall, ground saturation, etc. etc., all of which allow for an excellent short-term predictive model.

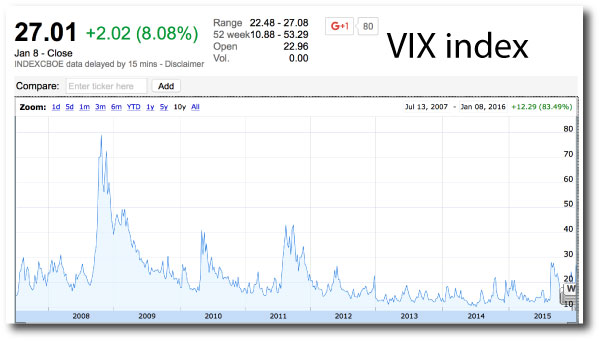

There is a provocative at-a-glance similarity of the stream flow process and the stock market volatility process, which is conveniently measured by the VIX index:

Analogies springing from the superficial commonality might be something interesting to think about when one is constructing predictive models for volatility, and indeed, the idea seems a bit more urgent at the beginning of this week than it was at the beginning of last…

For those interested, I’ve set up two seemingly unrelated prediction markets at our new website Metaculus. The first gathers forecasts of whether the California Drought will end by this spring. The second asks whether we’ll see an intra-day print of VIX>50 this year. We’re trying to juice some liquidity into these markets, so go ahead and and make your forecast…

March of Progress

For many years, and irregardless of the audience, one could profitably start one’s talk on extrasolar planets with an impressive plot. On the y-axis was the log of the planetary mass (or if one was feeling particularly rigorous, log[Msin(i)]), and the x-axis charted the year of discovery. The lower envelope of the points on the graph traced out a perfect Moore’s Law trajectory that intersected one Earth mass sometime around 2011 or 2012. (And rather exhiliratingly, Gordon Moore himself was actually sitting in the audience at one such talk, back in 2008.)

But now, that graph just makes me feel old, like uncovering a sheaf of transparencies for overhead projectors detailing the search for as-yet undiscovered brown dwarfs.

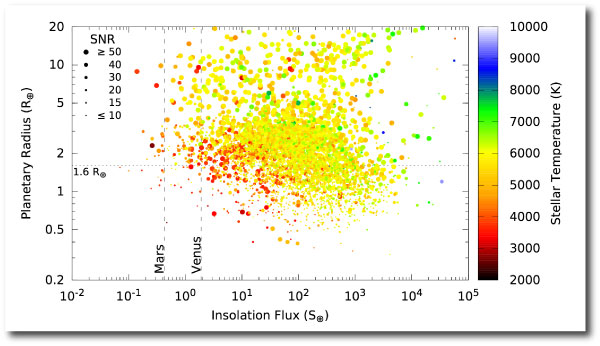

By contrast, a document that is fully-up-to-date is the new Kepler Catalog Paper, which was posted to arXiv last week. This article describes the latest, uniformly processed catalog of the full Q1-Q17 Kepler data release, and records 8,826 objects of interest and 4,696 planet candidates. This plot, in particular, is impressive:

For over a decade, transits were reliably the next big thing. At the risk of veering dangerously close to nostalgia trip territory, I recall all the hard-won heat and noise surrounding objects like Ogle TR-86b, Tres-1 and XO-3b. They serve to really set the plot above into a certain context.

Transits are now effectively running the exoplanet detection show. Much of the time on cutting-edge spectrographs — HARPS-N, HARPS-S, APF, Keck — is spent following up photometric candidates, and this is time-consuming work with less glamour than the front-line front-page searches of years past. Using a simple, admittedly naive solar-system derived mass-radius estimate that puts the best K-feet forward, the distribution of Doppler radial velocity amplitudes induced by all the Kepler candidates looks something like this:

Given that one knows the period, the phase, and a guess at the expected amplitude, RV detections of transiting planet candidates are substantially easier to obtain than blue-sky mining detections of low-amplitude worlds orbiting nearby stars. Alpha Centauri is closed for business for the next block of years.

Question is: During 2016, will there be a peer-reviewed detection of a Doppler-velocity-only planet with K<1 m/sec? Head over to Metaculus and make your prediction count.

Recipes

Spontaneous generation, the notion that life springs spontaneously and readily from inanimate matter, provides a certain impetus to the search for extrasolar planets. In the current paradigm, spontaneous generation occurs when a “rocky planet” with liquid water is placed in the “habitable zone” of an appropriate star.

The general idea has a venerable history. In his History of Animals in Ten Books, Aristotle writes (near the beginning of Book V):

Aristotle provides little in the way of concrete detail, but later workers in the field were more specific. Louis Pasteur, in an address given in 1864 at the Sorbonne Scientific Soiree, transcribes recipes for producing scorpions and mice elucidated in 1671 by Jean-Baptiste van Helmont:

Carve an indentation in a brick, fill it with crushed basil, and cover the brick with another, so that the indentation is completely sealed. Expose the two bricks to sunlight, and you will find that within a few days, fumes from the basil, acting as a leavening agent, will have transformed the vegetable matter into veritable scorpions.

If a soiled shirt is placed in the opening of a vessel containing grains of wheat, the reaction of the leaven in the shirt with fumes from the wheat will, after approximately twenty-one days, transform the wheat into mice.

There is a certain similarity to the habitable planet formula for the spontaneous generation of extraterrestrials — wet and dry elements combined for sufficient time give rise to life.

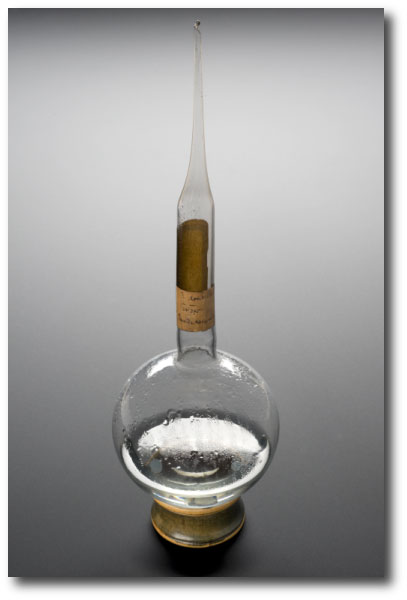

In his address, Pasteur goes on to describe his own forerunners of the Miller-Urey experiment, in which he sought to determine whether microbial life is spontaneously generated. He placed sterilized broth in swan-necked beakers that allowed the free circulation of air, but which made it difficult for spore-sized particles to reach the broth. His negative results were instrumental in dispatching the idea of Earth-based spontaneous generation of microbes from scientific favor.

A model for Enceladus? Before devising his swan neck flask experiments, Pasteur sealed flasks containing yeast water from air. The one above remains sterile more than 150 years on.

K2

Everyone’s heard the cliché about lemons and lemonade. NASA’s K2 Mission exemplifies it.

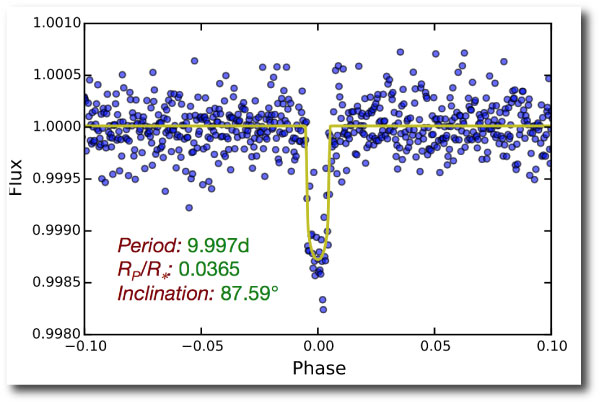

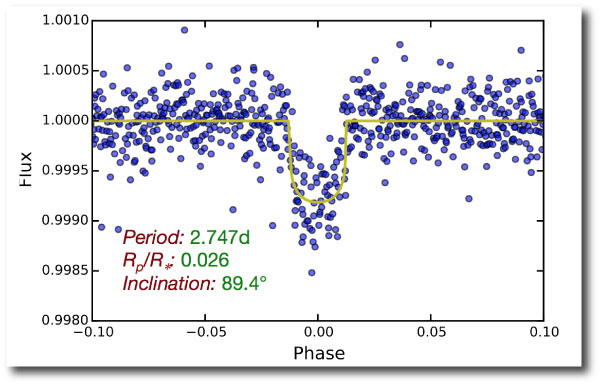

For brighter stars, the photometric light curves from K2 have precision on par with the original mission, and the data is completely free for everyone to look at. No secret repositories, no loose lips sink embargoed publications. Individual planets are so numerous that they are beginning to resemble the pages of names in a phone book. Six years ago, the light curve for EPIC 210508766 with its uninhabitable 2.747d and 9.997d super-Earths would have been cause for non-disclosure agreements and urgent Keck follow up. Now, given the ho-hum V=14.33, these planets will wind up as anonymous lines in a catalog paper — weights for gray scale dots in big data plots. Mere dimidia:

(EPIC 210508766 b and c, discovered earlier this week by Songhu Wang and Sarah Millholland)

A few years ago, I wrote a number of posts about a “valuation” equation for getting a quantitative assessment of the newsworthiness of potentially habitable planets. The equation folds qualities such as planetary size, temperature and proximity into a single number, which is in turn normalized by the dollar cost of the Kepler Mission.

The equation, when thoughtlessly applied to Earth, nearly got me into serious hot water when the now-defunct News of the World ran a story with it (which stayed, fortunately, behind a pay wall).

Now that Kepler’s prime mission has been complete for a substantial period, it’s interesting to calculate the values implied by the equation for the up-to-date table of Kepler’s KOI candidates. The cumulative sum runs into the tens of millions of dollars, with single objects such as KOI 4878.01 exceeding $10M. Such worlds are truly the candidates that the Kepler Mission was designed to find.

With K2, which has many bright M-dwarfs within its sites, it’s quite plausible that some very high-profile planets will soon turn up. I’ve set up a K2 prediction market at metaculus.com that canvases the likelihood that such a discovery is imminent…

Sign up and make your prediction count!

The IAU Exoplanet Names

If nothing else, the extrasolar planets comprise a thoroughly alien cohort, albeit one that is hitched awkwardly to a naming scheme of utilitarian expedience: Tres-4b, Gliese 876e, HD 149026b, and so forth.

When it comes to exoplanets, I’m somewhat chagrined to realize that I fall into the old timer category, and so predictably, back in the old days, I stuck up for the conservative, default naming convention. In this post on exoplanet names back in 2008, I wrote:

A sequence of letters and numbers carries no preconception, underscoring the fact that these worlds are distant, alien, and almost wholly unknown — K2 is colder and more inaccessible than Mt. McKinley, Vinson Massif or Everest.

The International Astronomical Union, however, just issued official crowdsourced names for 31 exoplanets.

Some of them might take a some getting used to. Fortitudo, Orbitrar, Intercrus. “Son, that’s not 51 Peg b, that’s Dimidium.”

So will the names come into general use? I’ve set up a prediction market at our new website Metaculus to determine whether or not it’s likely:

www.metaculus.com/questions/38/

What do you think? Sign up and make your prediction count…

How did they get there?

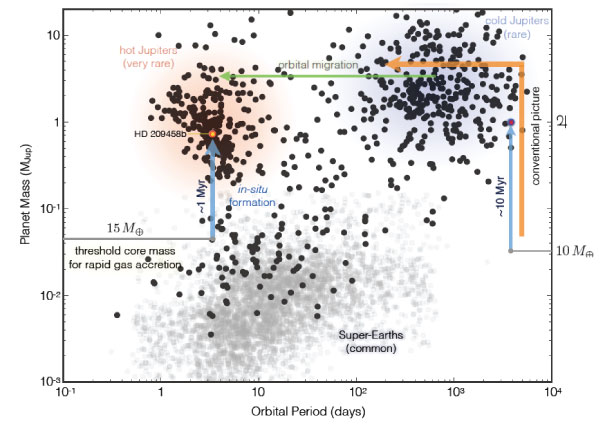

There are of order 500 million hot Jupiters in the Milky Way. Swollen and massive, with blisteringly short periods, they crowd the tables and the diagrams showing extrasolar planets. The first of their number were career-cementing front page news, trophies of planet roving planet hunters. Two decades on, they slip into the census with little fanfare and less notice.

Conventional wisdom holds that hot Jupiters form at large, Jupiter-like distances, where water ice is stable and where the orbital clock runs slowly. Then they migrate radially inward, either gradually, by interacting with the disk that produced them, or, even more gradually, via the Kozai process, or perhaps, violently, as a consequence of dynamical instabilities that toss giant planets to and fro.

When the first hot Jupiters were discovered, their presence was so strange, so unpredicted and so uncomfortable that there was a certain need for a point of contact with the familiar. It seems more sensible that a planet should form in the right environment and then go astray, rather than defy odds and logic to emerge spontaneously in a location where it obviously shouldn’t be. It’s a short leap from the Copernican principle to the idea that the Solar System has no special distinction. We have nothing orbiting at forty days, not to speak of four.

Yet there is a tantalizing gap in the mass-period diagram that hints that short-period super-Earths that reach fifteen or more Earth masses might engage in rapid gas accretion. Such promotions need happen less than once in a hundred tries. In the spirit of trying to go against the grain, in the perverse hope of eliciting a paradigm shift, Konstantin, Peter B. and I have been working to make the case that many hot Jupiters might just form where they’re found.

The details are all in a paper that we just posted on arXiv.