Image Source.

The discovery of new planets is rarely clear cut. No sooner does a new world (Vesta, Neptune, Pluto) emerge, than the wrangling for the credit or the naming rights starts. And it’s usually possible to find a reason why the prediction (or even the planet itself) wasn’t really valid in the first place.

The trans-Uranian planet predicted by Urbain J. J. Le Verrier and John Couch Adams happened to coincide quite closely with Neptune’s actual sky position in September 1846, but the orbital periods of their models were too long by more than 50 years. Le Verrier’s predicted planetary mass, furthermore, was too large by nearly a factor of three, and Adams’ mass prediction was off by close to a factor of two.

In England, following the announcement of Neptune’s discovery, and with the glory flowing to Le Verrier in particular and France in general, the Rev. James Challis and the Astronomer Royal George Airy were denounced for not doing enough to follow up Adams’ predictions, “Oh! curse their narcotic Souls!” wrote Adam Sedgwick, professor of geology at Trinity College.

Nowadays, with the planet count up over 200, the prediction and discovery of a new world doesn’t quite carry the same freight as it did in 1846. No editorial cartoons, no Orders of Empire, and no extravagant public praise to the discoverer, such as that heaped by Camille Flammarion on Le Verrrier, who wrote, “This scientist, this genius, has discovered a star with the tip of his pen, without other instrument than the strength of his calculations alone!”

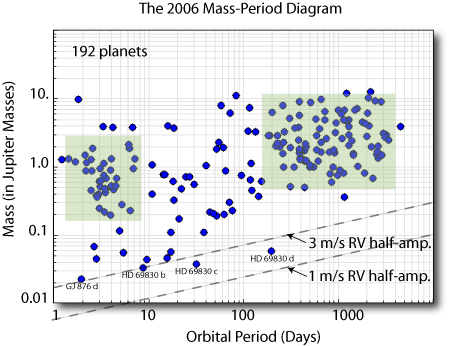

Nevertheless, I don’t want to be shoehorned into the ranks of the “narcotic souls” as a result of not properly encouraging the bringing to light of any potential planetary discoveries in the systemic catalog of real stellar radial velocity data sets. As of Dec. 30th, 2006, over 3,680 orbital fits have been uploaded to the systemic backend. It’s definitely time to start sifting carefully through the results that the 518 registered systemic users have produced. Over the next few weeks we’ll be introducing a variety of analysis and cataloging tools that will make this job easier, but there are some interesting questions that can be answered right away. Foremost among these is: what are the most credible (previously unannounced) planets in the database?

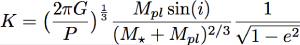

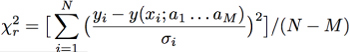

The backend uses the so-called reduced chi-square statistic as a convenient metric for rank-ordering fits:

In the above expression, N is the number of radial velocity data points, and M is the number of activated fitting parameters. As a rule of thumb, a reduced chi-square value near unity is indicative of a “good” fit to the data, but this rule is not exact, and should hence be applied with caution. The observational errors likely depart from a normal distribution, and more importantly, the tabulated errors don’t incorporate the astrophysical radial velocity noise produced by activity on the parent star. Furthermore, it’s almost always possible to lower the reduced chi-square statistic by introducing an extra low-mass planet.

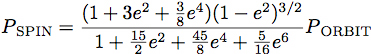

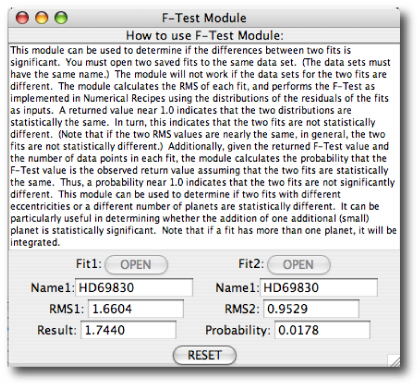

Eugenio recently implemented the downloadable console‘s F-test, which can provide help in evaluating whether an additional planet is warranted. The F-test is applied to two saved fits and returns a probability that the two fits are statistically identical. As an example, pull up the HD 69830 data set and obtain the best two planet fit that includes the 8.666-planets and 31-day planets. Save this fit to disk. Next, add the 200-day outer planet and save the resulting 3-planet fit to disk (using a separate name). Clicking on the console’s F-test button allows the F-test to be computed using the two saved fits:

In the case of HD 69830, there’s a 1.7% probability that the 2-planet fit and the 3-planet fit are statistically identical. This low probability indicates that the third planet is providing a significant improvement to the characterization of the data. It’s likely really out there orbiting the star.

So here’s the plan: Let’s comb through the systemic “Real Star” catalog, and find the systems that (1) contain an unannounced planet(s) in addition to the previously announced members of the system (see the exoplanet.eu catalog for the up-to-date list). (2) have a F-test probability of less than 2% of being statistically identical, and (3) are dynamically stable for at least 10,000 years. If you find a system that meets these requirements, post your findings to the comments section of this post.

Disclaimer: this exercise is for the satisfaction of obtaining a better understanding of the planetary census, and also for fun. When the planets do turn up, I’m going to sit back with a bottle full of bub and enjoy any scrambles for priority from a safe distance.

Happy New Year, y’all!