East Rock rises abruptly from the flat New Haven city streets that surround it. Approaching from the south or the west, its diabase ramparts rear up forbiddingly.

While most of the East Coast’s ranges date to the continental collisions that assembled Pangea, the igneous intrusions and the sedimentary rocks of central Connecticut are roughly half as old and stem from Pangea’s demise. East Rock Park is a Jurassic Park, and two hundred million years ago, the rifts that eventually grew to become the Atlantic Ocean were opening just south of town. The rift valley floor was sinking, sediment was accumulating to fill the growing depression, and the sill of lava that eventually solidified into East Rock was squeezing out in a thick viscous sheet.

Several miles north of East Rock, an extensive road cut reveals layers of sediment from near the Jurassic-Triassic boundary. Beds of reddish sandstones and fused conglomerates of mud and pebbles are tilted at an angle of about 10 degrees, a remnant of the sinking and foundering that the rock layers suffered after they formed. The strata are varied and clearly visible, representing sediments that accumulated in a rift valley that alternated between a seasonal playa during dry periods and long-lived lake bed during wet periods.

Near the dawn of the Jurassic, New Haven was located in the tropics. During rain-soaked epochs, the shores of the rift lakes were a year-round riot of green with pterosaurs soaring in the skies. Perhaps there was nothing overt in those long-departed scenes to suggest that the end-Triassic extinction was either near or was already underway. And now, two hundred million years later, the layered record of ancient climate change stands mute and unvarying as the engines of loaded dump trucks roar and strain against the freeway grades.

A close look at the road cut shows a banding pattern that starts to repeat as one ascends from the lower exposed layers at the left of the photo to the upper exposed layers on the right. A look at the literature indicates that the rate of deposition in Central Connecticut 200 million years ago was about 1 millimeter of sediment per year, so the span recorded in the exposure is about 20,000 years. The repetition reflects one precession cycle of Earth’s spin, which dictates how the seasons align with the varying distance from the Sun stemming from the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit.

The sedimentary record in the New Haven area from the period of Pangea’s rifting is continuous over something like 20 million years, and the tilted layers of rocks fill Connecticut’s central valley to depths measured in miles. Cores drilled through this colossal lens of sediment reveal that Earth’s ancient orbital eccentricity variations are faithfully recorded in the strata.

In the course of an afternoon, with a laptop and the Rebound code, one can integrate the full Solar System back to the moment when the hardened lava that makes up present-day East Rock was glowing toothpaste-red and pushing its way into the then-newly lithified strata.

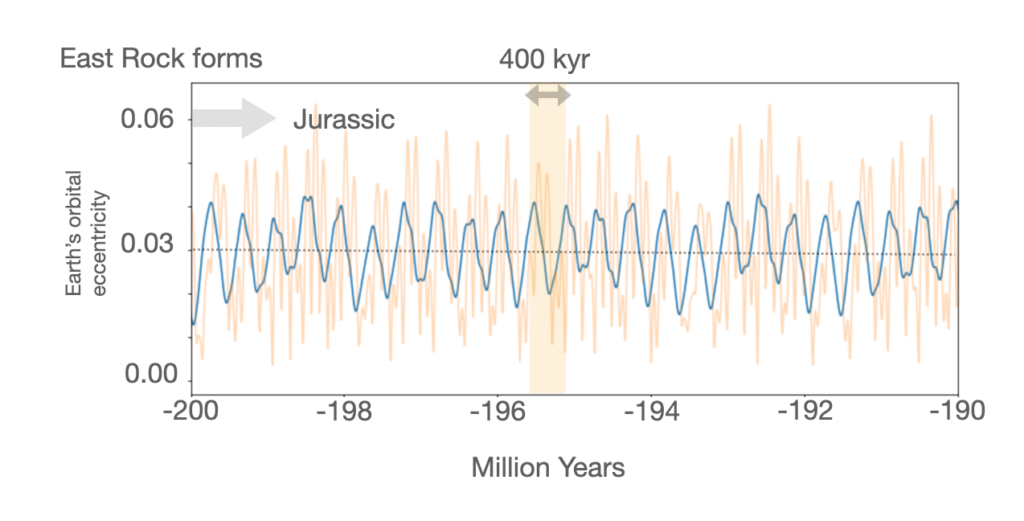

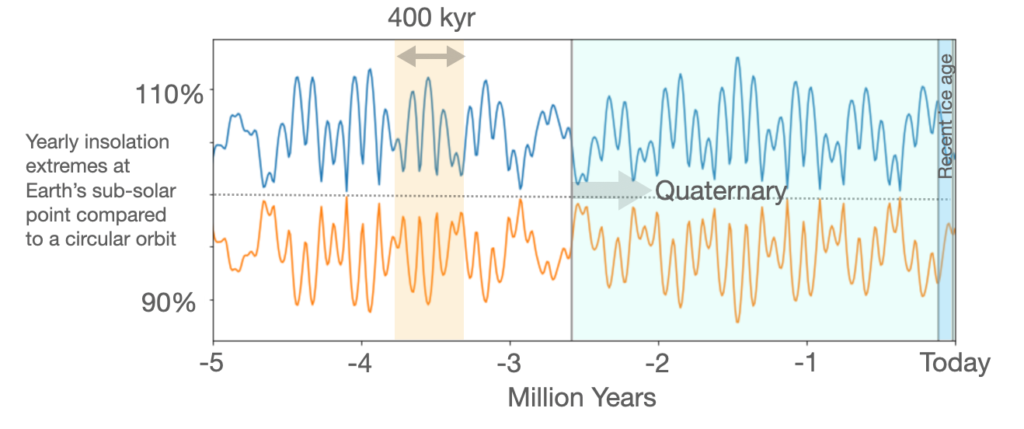

Looking back over the past five million years, Earth’s secular eccentricity variations are plainly apparent. In particular, the ~400 kyr envelope produced by the beating of the Venus-dominated g2~7.2”/yr and Jupiter-dominated g5~4.3”/yr secular frequencies is clearly visible.

This ~400 kyr (or more precisely, 405 kyr pattern) has been remarkably stable over Earth’s history. Running the clock back to the dawn of the Jurassic 200 million years ago, it shows no real change in character from the present. The plot just below runs for 10 million years forward from the formation of East Rock. A low-pass filter has been applied to the full eccentricity variation (shown by the light orange curve) to show the 400 kyr variation swinging up and down. Just as it does today.