HAT-P-13c could easily wind up being 2010’s version of HD 80606b — a long-shot transit candidate that pans out to enable extraordinary follow-up characterization, while simultaneously allowing small-telescope ground-based observers to stunt on the transit-hunting space missions.

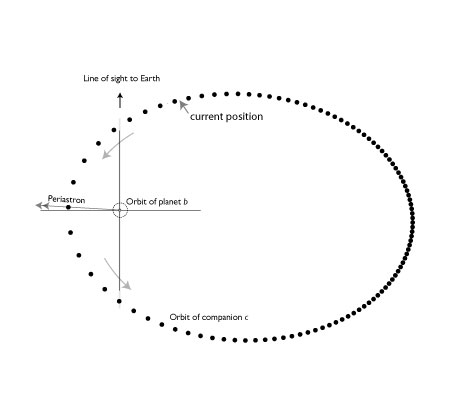

The HAT-P-13 system has already gotten quite a bit of oklo.org press (see articles [1], [2], and [3]). It generates intense interest because it’s the only known configuration where a transiting short-period planet is accompanied by a long-period companion planet on an orbit that’s reasonably well characterized by radial velocity measurements. Right after the system was discovered, we showed that if the orbits of the two planets are coplanar, then one can probe the interior structure of the transiting inner planet by getting a precise measurement of its orbital eccentricity. The idea is that the system has tidally evolved to an eccentricity fixed point, in which the apsidal lines of the two planets precess at the same rate. Both the precession rate and the inner planet’s eccentricity are single-valued functions of the degree of mass concentration within the transiting planet.

Early this year, Rosemary Mardling expanded the analysis to the situation where the two planets are not orbiting in the same plane (her paper here). If there is significant non-coplanarity, the system will have settled into a limit cycle, in which the eccentricity of the inner planet and the alignment angle of the apsidal lines cycle through a smoothly varying sequence of values. The existence of a limit cycle screws up the possibility of making a precise statement about planet’s b’s interior, even if one has an accurate measurement of the eccentricity.

When one ties all the lines of argument together, it turns out that there are two different system configurations that satisfy all the current constraints. In one, the planetary trajectories are nearly co-planar, with the inclination angle between the two orbits being less than 10 degrees. If the system has this set-up, then we’ll be in good position to x-ray the inner planet. In the alternative configuration, the orbital planes have a relative inclination of ~45 degrees, and the limit cycle will hold.

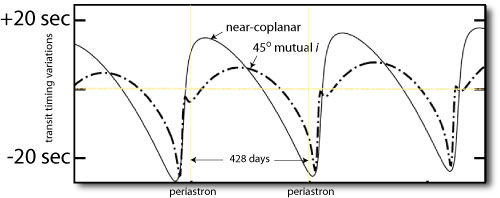

Matthew Payne, a postdoc at Florida, along with Eric Ford, have done a detailed examination of the transit timing variations that the two configurations will produce. (Transit timing variations — or TTV as all the hipsters were referring to them last week at SXSW — have been all the rage during the last few years, but have so far generated more buzz than results. That should change when HAT-P-13 takes the stage.) Payne and Ford found that timing variations should amount to tens of seconds near the periastron of planet c, which should in turn allow a resolution of whether the system is co-planar or not:

HAT-P-13 is a tough system for small-telescope observers to reach milli-magnitude precision at a cadence high enough to accurately measure the transit timing variations. Nevertheless, the top backyard aces will be giving it a go. Bruce Gary has reactivated the AXA especially for the event, and University of Florida grad student Ben Nelson has written a campaign page for Lubos Brat’s Tresca database. The best transits for detecting TTV will be occurring during April and May. This is an opportunity to really push the envelope.

If the system turns out to be close to coplanar, then there’s a non-negligible probability (of order 5-10%) that planet c will be observable in transit. The transit window is centered on April 12th, and is uncertain by a few days to either side. Small telescope observers will definitely be competitive in checking for the transit. In an upcoming post, we’ll take a look at the details and the peculiarities of this remarkable opportunity.

Does CoRoT 7b,c qualify as another system with a transiting planet and non-transiting close companion?

Or are those planets so close in that star-planet interactions swamp the planet-planet ones?

@cwmagee

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think the main thing that makes HAT-P-13 more attractive than CoRoT-7 is that the planets at CoRoT-7 are in perfectly circular orbits to as far as we can detect. HAT-P-7’s planets are both eccentric, and with aligned perihelia, and it is that unique situation that is absent from CoRoT-7 that may play into our favor for probing the interior of HAT-P-13 b.

That should be “HAT-P-13” not “HAT-P-7” ¬_¬

@cwmagee

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think the main thing that makes HAT-P-13 more attractive than CoRoT-7 is that the planets at CoRoT-7 are in perfectly circular orbits to as far as we can detect. HAT-P-7’s planets are both eccentric, and with aligned perihelia, and it is that unique situation that is absent from CoRoT-7 that may play into our favor for probing the interior of HAT-P-13 b.

Yes, CoRoT-7b & c is another system with two published planets and one transiting planet. Currently, we expect it to be much easier to detect TTVs of HAT-P-13b for two reasons…

1. Based on the published Doppler observations, we believe that HAT-P-13c has a large eccentricity and thus should cause a sizable perturbation to the transit times over a fairly short period of time near the time of periastron of the outer planet.

2. The transit of HAT-P-13b is deep enough that the transit time can be measured fairly well using even modest ground-based observatories.

Revised parameters for HAT-P-13 c!

http://arxiv.org/abs/1003.4512

“The next inferior conjunction of c, when a transit may happen, is expected on JD 2,455,315.2 +/- 1.9 (centered on UT 17h 2010 April 28).”

Turns out b is well aligned with the star and that there is a long-term RV drift suggesting of a third companion.