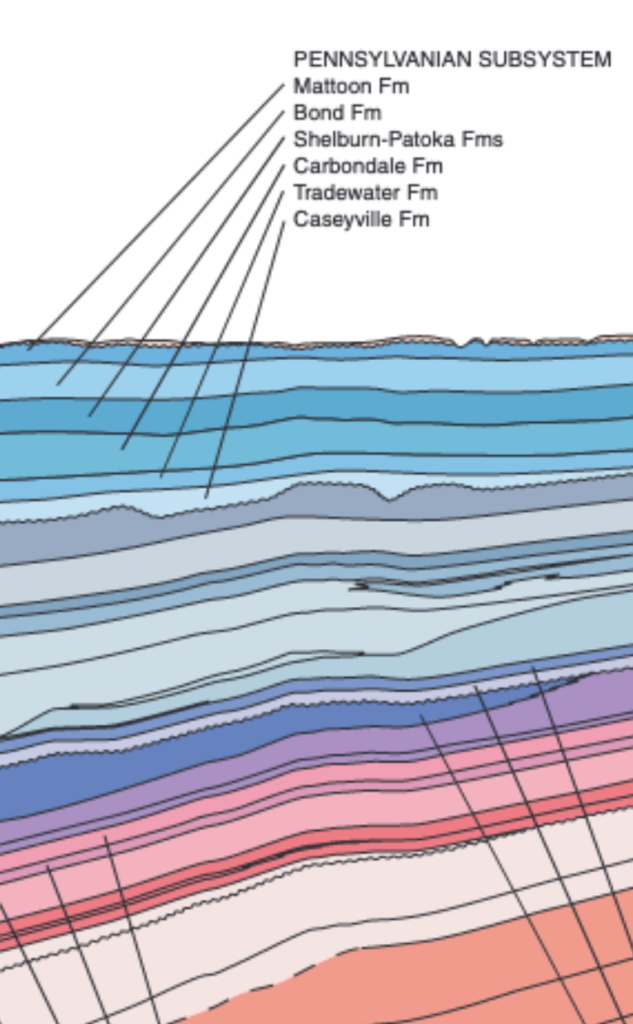

Geologically speaking, not much has happened in Illinois since the Permian. In particular, in the ultra-flat vicinity of Urbana where I grew up, there is no exposed bedrock at all. If one takes the effort to dig down through meters of topsoil and glacial till, one eventually hits gray, unmetamorphosed 320-million year old sediments from the Carboniferous — the Mattoon Formation — the crumbly picture of a disappointing drill core.

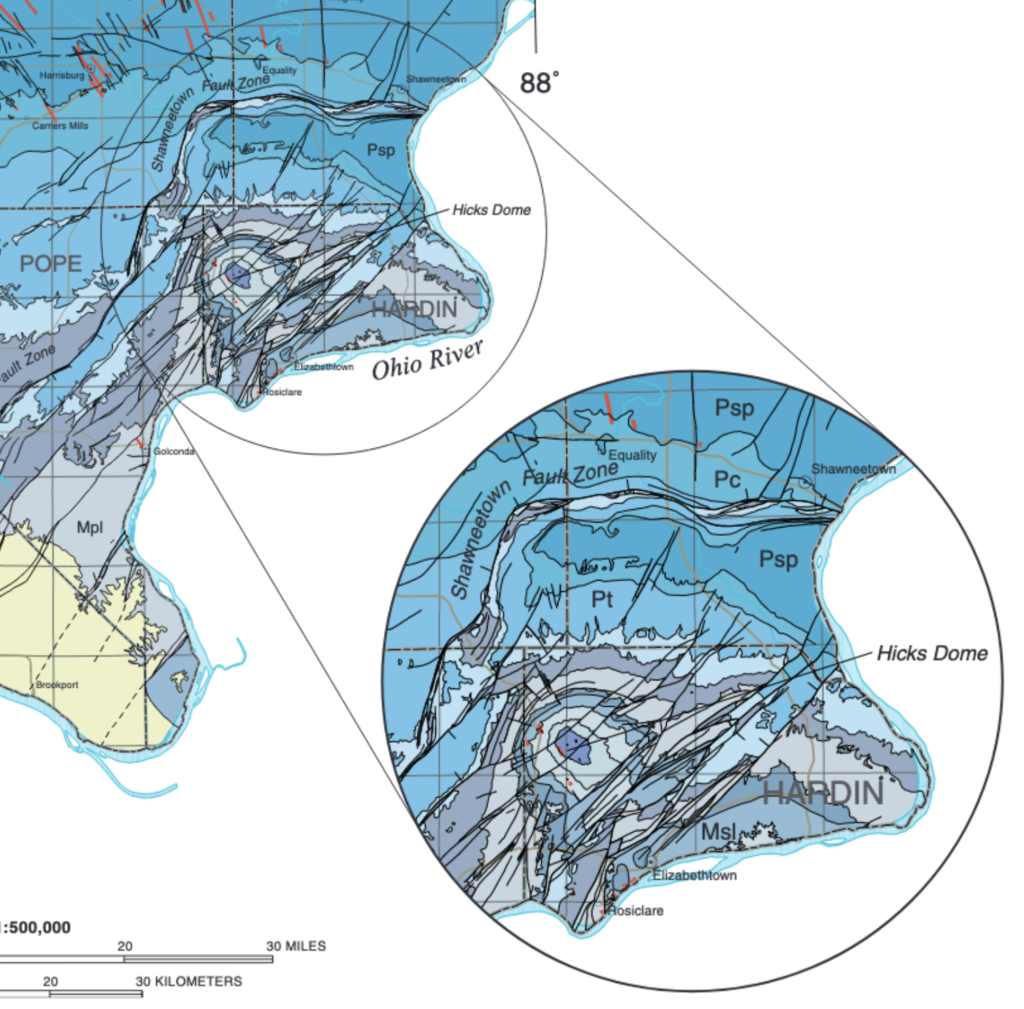

Something about those miles of dull strata directly underfoot instills a vicarious appeal into the IGS maps for the entire state. And while they are dominated by the vast bland extent of the coal-rich Illinois basin, the margins of the map hint at strange and exotic features, including one, Hicks Dome, that’s so weird that it merits its own circular inset.

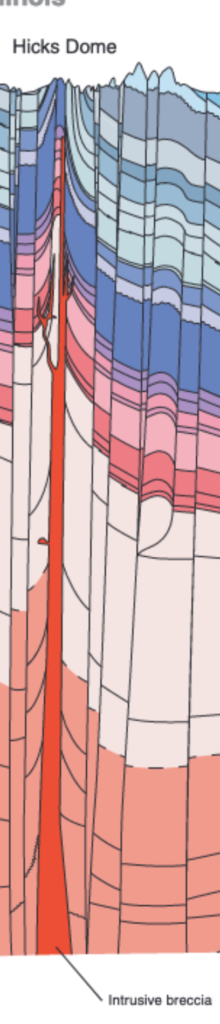

The southeastern tip of Illinois is riddled with faults, and pocked by a mysterious, crater-like 275-million year old blemish that is still clearly visible in aerial photographs. The strata that comprise this feature — the Hicks Dome — were pushed up thousands of feet by a carbon dioxide-driven explosion that brecciated the rock miles below and squeezed dikes of lava through cracks toward the surface.

The resulting igneous rocks, which are colored red in the diagram just above, can be extracted from drill cores. Mineralogical tests indicate that the lava ascended at least 25 km from a source of origin in the upper mantle. Then later, during the Jurassic, geothermally heated brines seeped through the faults that shattered the sediments and interacted with limestone to form fabulous fluorite crystals.

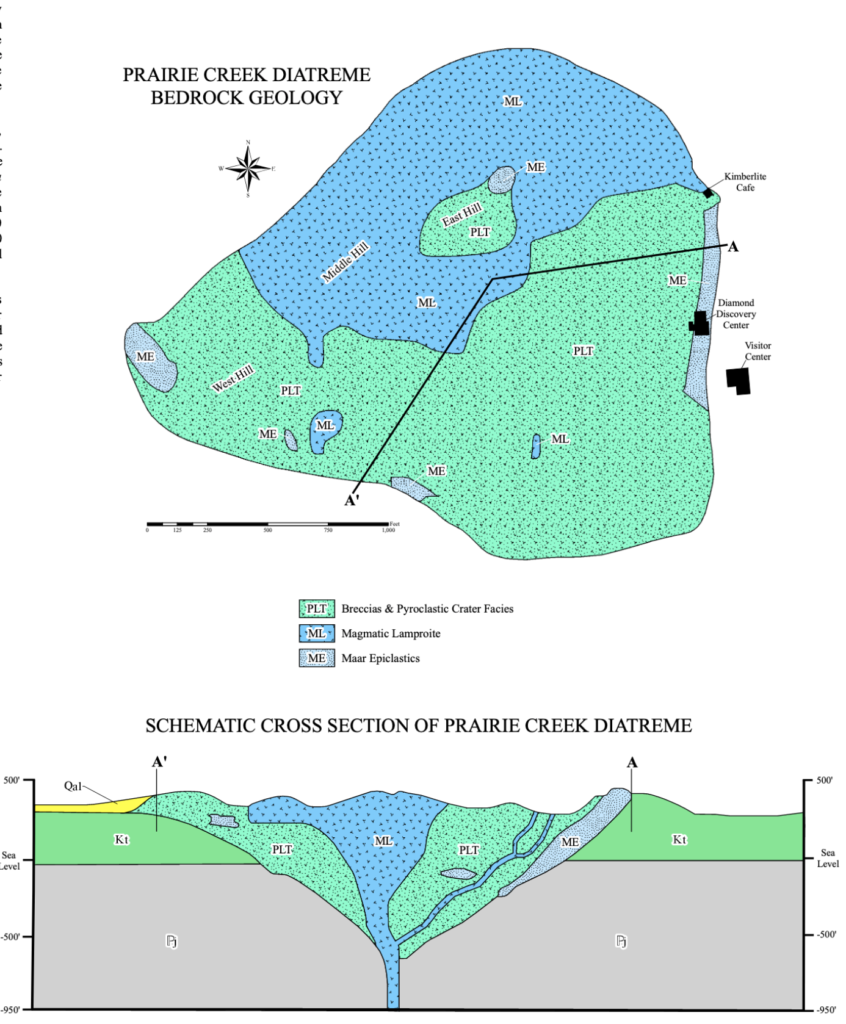

An even more remarkable example of a deep-Earth intrusion is located in Arkansas, 383 miles southwest of Hicks Dome. The Prairie Creek Diatreme, more evocatively known as the Crater of Diamonds, is a 106-Myr old igneous pipe filled with solidified lamproite lava that was driven upward (as also occurred at Hicks Dome) by exsolving CO2 gas from a source at least 100 miles down. The crater, moreover, is indifferently salted with actual diamonds, including the occasional big-deal gem.

Diamonds are metastable when removed from deep mantle conditions, and so in order for them to survive a lava-soaked mix-mastered trip to Earth’s surface, the transport has to be rapid. The lamproite that brought up the diamonds must have smashed its way through a hundred miles of rock with a vertical velocity of order a hundred miles per hour, a marshaling of forces that is undeniably impressive, and indeed, at first glance, completely non-intuitive.

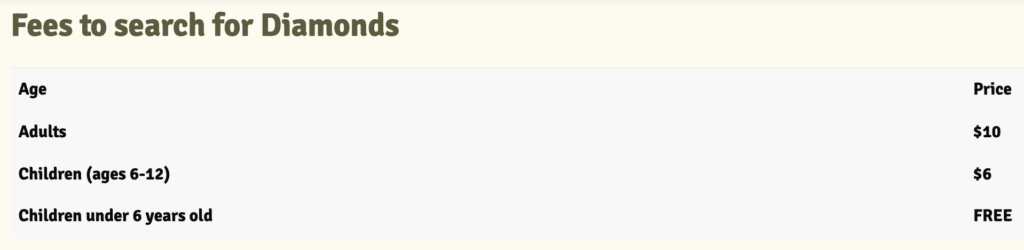

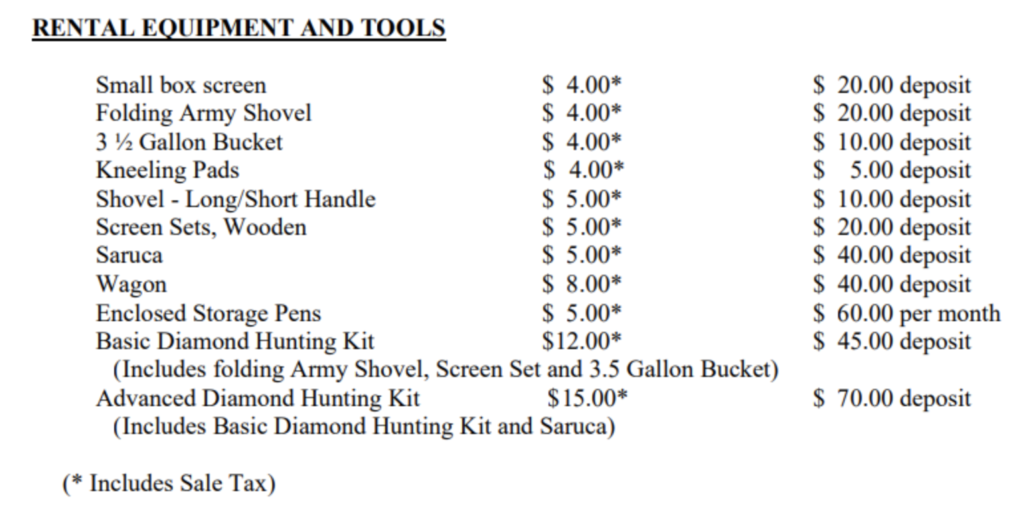

Satisfyingly, a hundred and six million years after the cryptoexplosion, Arkansas is running the lamproite pipe as a State Park, offering end-runs around de Beers at very reasonable rates:

Earth’s last diamond-bearing eruptions occurred tens of millions of years ago. It’s a good thing they aren’t every-day occurrences. Methane gas, however, is currently causing new-school cryptoexplosions that leave ominous lake-filled craters in the permafrost of the Siberian tundra.

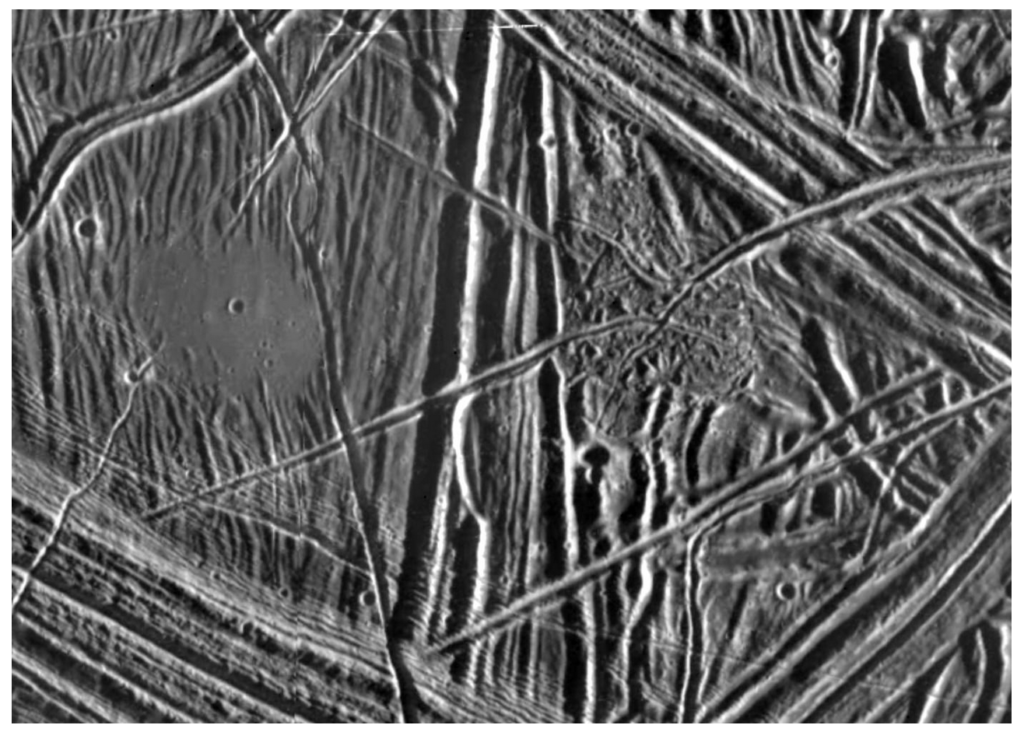

On Earth, the crypto prefix can generally be detached from cryptoexplosions once the techniques of laboratory and field geology have been brought to bear. Kimberlite eruptions may seem superficially crazy, but the basic mechanism of their operation is increasingly well understood. Truly mysterious explosions need to occur off Earth, in locations where it’s not yet possible to go in and root around after the fact…