There are a lot of good books in the public domain. In Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, I’ve always been intrigued by the description of…

…the yellow book that Lord Henry had sent him. What was it, he wondered. He went towards the little pearl-coloured octagonal stand, that had always looked to him like the work of some strange Egyptian bees that wrought in silver, and taking up the volume, flung himself into an armchair, and began to turn over the leaves. After a few minutes he became absorbed. It was the strangest book that he had ever read. […] The style in which it was written was that curious jewelled style, vivid and obscure at once, full of argot and of archaisms, of technical expressions and of elaborate paraphrases […] There were in it metaphors as monstrous as orchids, and as subtle in colour.

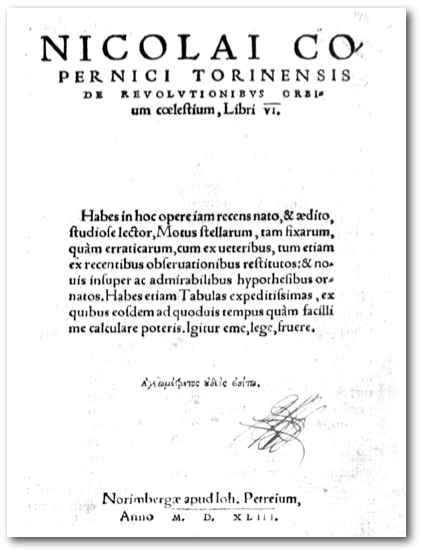

Google books, with its vast digitized sea, imbues the esoteric with the convenience of a TV dinner. While sitting at the gate in O’Hare waiting for the flights that would take me to the Torun Conference a few years ago, it occurred to me that it might be cool if my talk had a scan from an original edition of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. A minute later, it had been pulled from the ether by my computer.

(A Rebours makes decidedly better reading. While Copernicus’ great work is at once, full of argot, archaisms, and technical expressions, it is wholly devoid of metaphors as monstrous as orchids, and as subtle in colour.)

With millions of digitized books, one can step away from trying to find those individual bits of half-remembered ephemera, and instead treat all the words in all the books statistically. There was an article in Science last week (Michel et al. 2010) which received lots of press, and which contains a link to Google’s Ngram viewer.

An “Ngram” is a neologism for a specific string of N words. The idea is that you can trace cultural trends by charting the frequency with which words appear in books. For example, for 5 million books published between 1800 and 2000, the frequencies of appearance of 61 Cygni, Alpha Centauri, Proxima Centauri, Beta Pictoris, and 51 Pegasi are:

61 Cygni, which, in 1838 was the first star to have its distance correctly measured, was a marquee attraction during the Nineteenth Century. As a result of Thomas Henderson’s timidity in publishing his parallax, it took Alpha Centauri, which is closer, brighter, and more alluring, more than 80 years to surpass 61 Cygni’s fame. Proxima, which was discovered in 1915, has never managed to be as popular as Alpha, and, until recent decades, has struggled to keep up with 61 Cygni. Beta Pictoris makes its debut in 1983, and 51 Pegasi starts turning up after 1995.

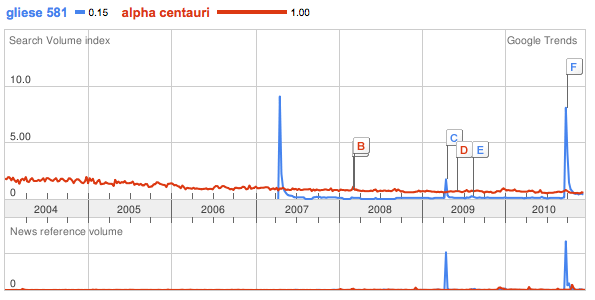

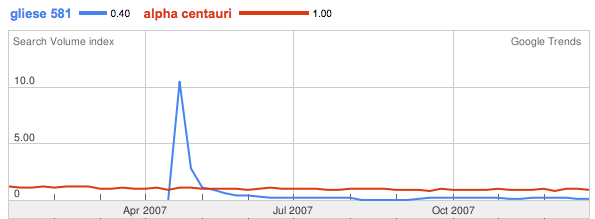

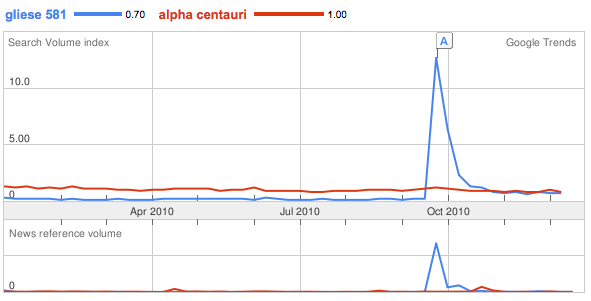

As a visit to Borders will quickly confirm, books are fast losing their status as a cultural linchpin. For topics of current interest, Google trends is more the destination of choice. Here, one can follow the share of the total global search volume that a particular N-gram elicits. News reference volume is also charted. Among the stars of interest, there is a steady stream of searches on Alpha Centauri. Against this background, there are three rather notable spikes associated with Gliese 581, which, prior to 2007, languished in complete obscurity.

After the 2007 spike, Gliese 581’s mojo quickly faded to a small fraction of Alpha Centauri’s.

Interestingly, though, the 2010 pattern is behaving differently. In the months following the most recent spike, Gliese 581 has been running neck and neck with Alpha C in competition for the world’s notice.

Yay! My money is on Alpha Centauri for the win! Because she is our neighbor and it is the holidays.

(On a slightly off topic note: I thought this might be of interest for Systemic fans: http://www.planethunters.org/science – the Kepler data is being released to the public!!!)

Talking of 61 Cygni, what are the current limits on planets orbiting either of the two stars? I recall there was an early history of astrometric claims but this didn’t come to anything.

Pingback: Deep Space and Human Motivations