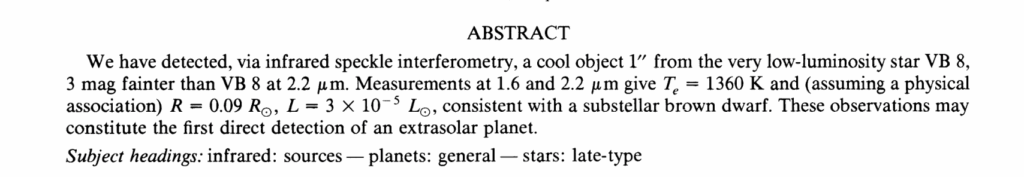

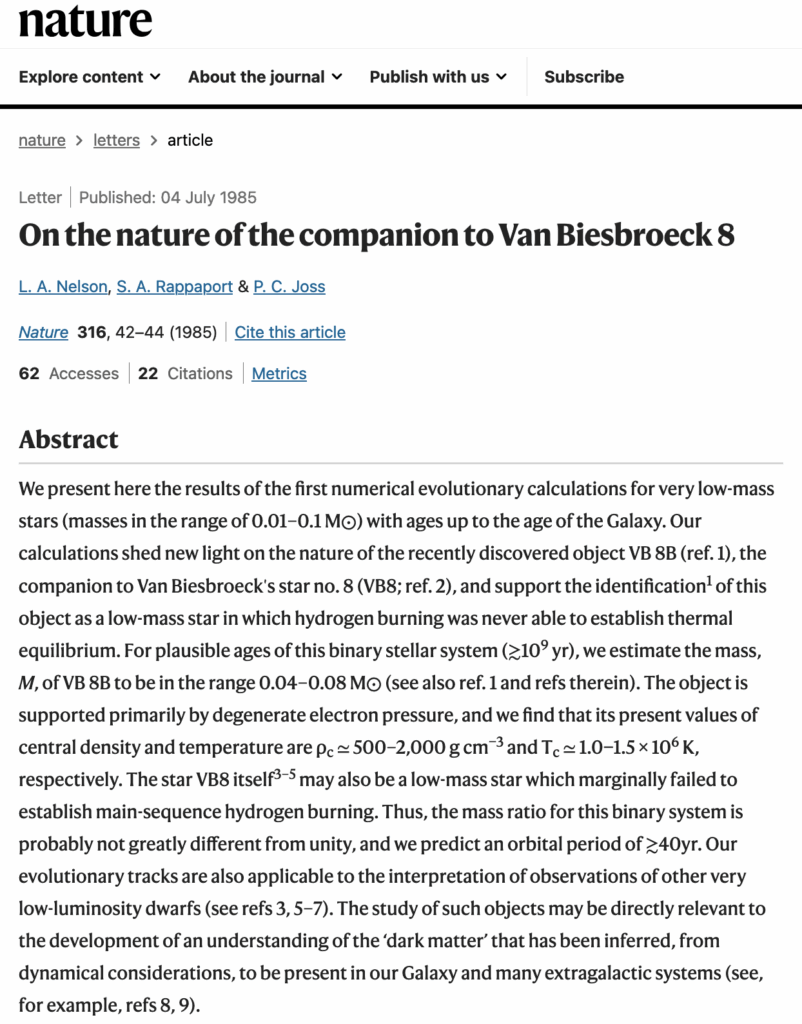

In 1991, brown dwarfs had a sketchy reputation. They were variously held responsible for everything from killing the dinosaurs to preventing the galactic rotation curve from decreasing in a sensible manner. A few years prior, there had been a high-profile discovery of the “first” brown dwarf, VB-8b, which was spotted orbiting VB-8 — a low mass red dwarf twenty-one light years distant that is part of the nearest known quintuple star system.

That generated a lot of excitement, a lot of analysis, even a conference. Here’s a Nature article that held forth on the cool new object. According to the abstract, the authors even racked up their own “first” (on the theoretical side):

Unfortunately, however, VB-8b vanished upon further scrutiny.

The lack of any known brown dwarfs served to elevate their edgy mystery. The idea that one might actually be lurking in the near-solar neighborhood, nearer, perhaps than the closest stars, held a weird attraction. It was something I could glom onto. It was not like L1551.

In August of 1991, there was a conference at UCSC on star formation, and one of the speakers was Ben Zuckerman from UCLA. I remember that it was a day when the thick coastal fog didn’t lift. Everything outside was gray and dripping wet. Zuckerman showed the results of different ongoing searches for brown dwarfs. I found myself suddenly snapped to attention. He was discussing the conclusions from a paper that they’d just gotten accepted and which was in press. It was eventually published in February of ’92.

The take-away was that brown dwarfs were probably very rare. That was a disappointment, and remarkably, given the lethargy I’d been showing toward astronomy generally, I was actually disappointed. I was surprised at how much I wanted the brown dwarfs to be looming out there. Preferably nearby.

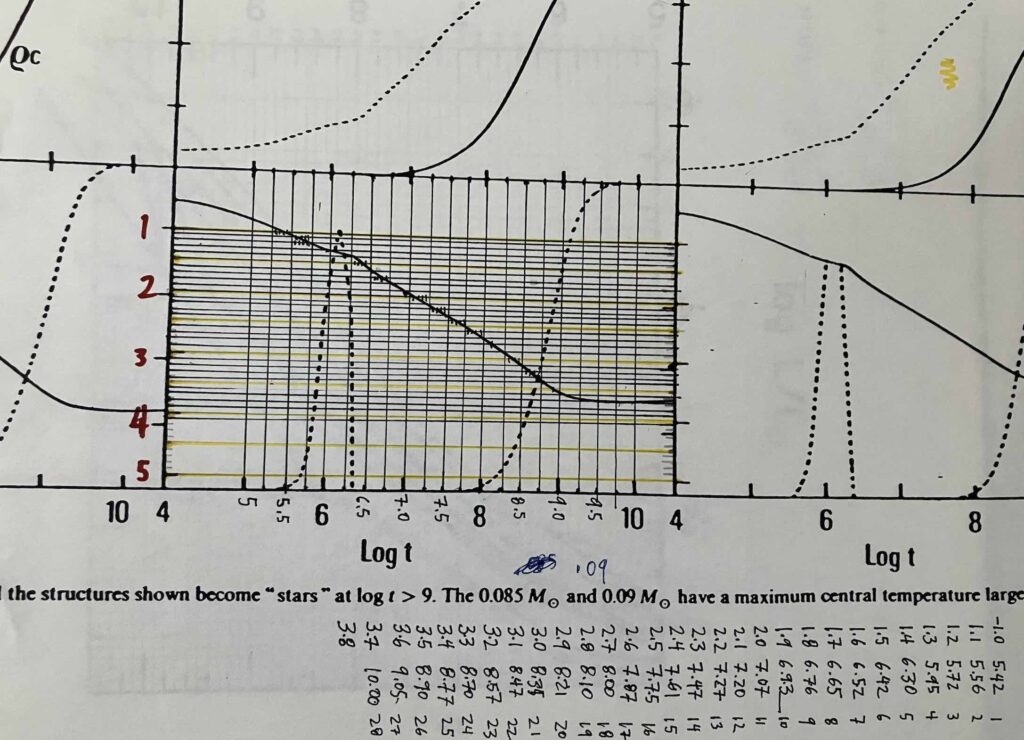

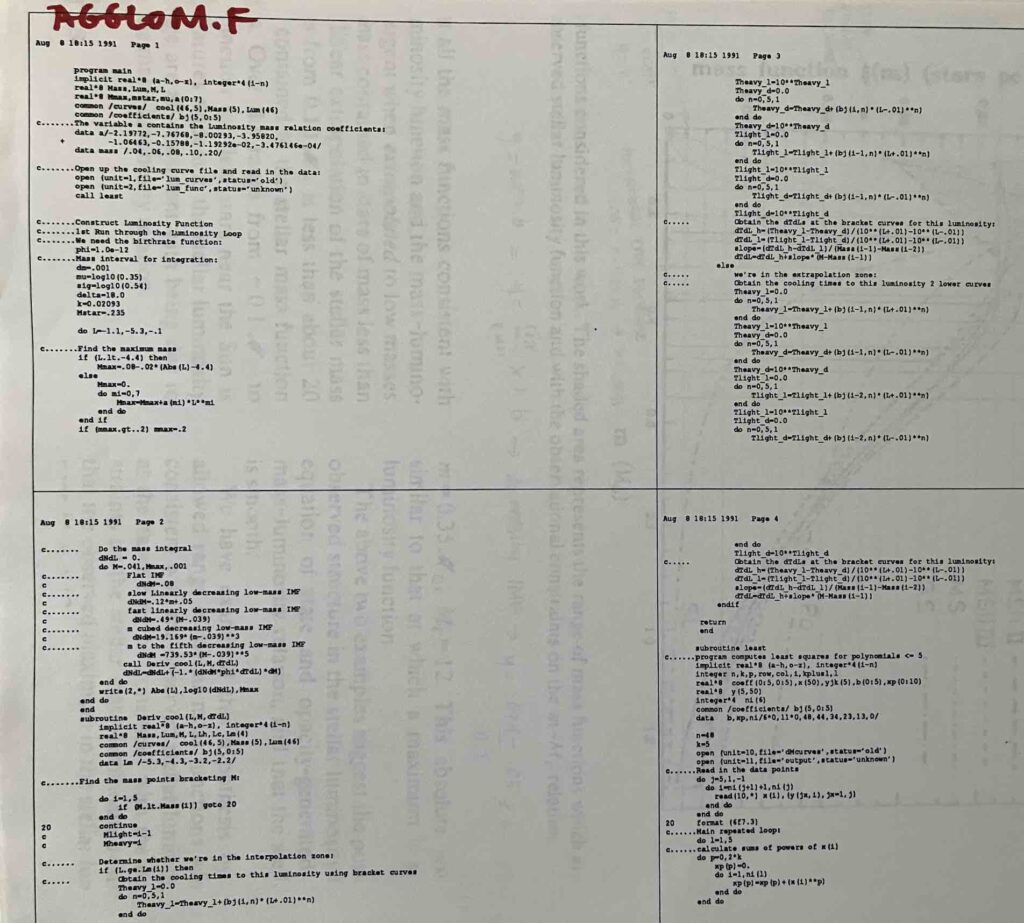

As Zuckerman showed his transparencies, I suddenly had a flash of an idea — maybe the first concretely independent and actionable idea that I’d had up to that moment. I had the intuitive feeling that the brown dwarfs weren’t showing up in the surveys because they were too dim. The cooling curves needed to be taken properly into account. They were out there, yes! but they were beneath the threshold of detection. And this was something moreover, that wasn’t just limited to a vague feeling. It could be calculated! I was galvanized into action. As soon as the session let out, I went to the Lick Observatory library to find the ingredients that I needed. Evolutionary models for low mass objects near the bottom of the Main Sequence. Bolometric corrections. The results of red dwarf surveys. I started working feverishly.

———–

Recently, in going through old boxes, I found the notes from that effort, a time capsule from decades ago.

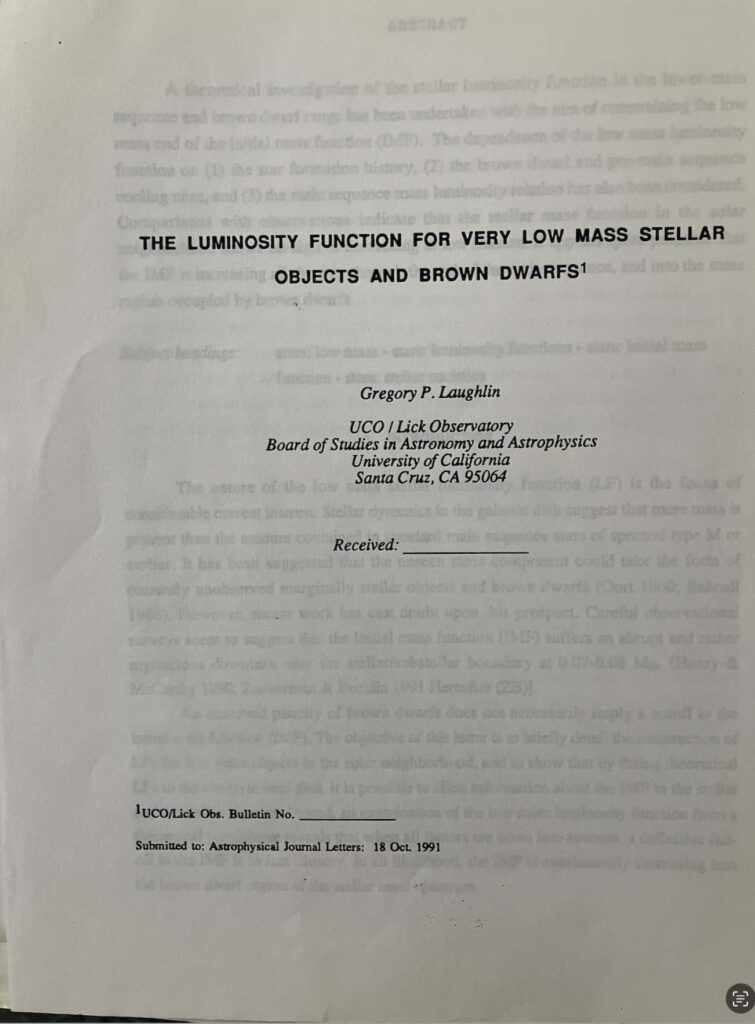

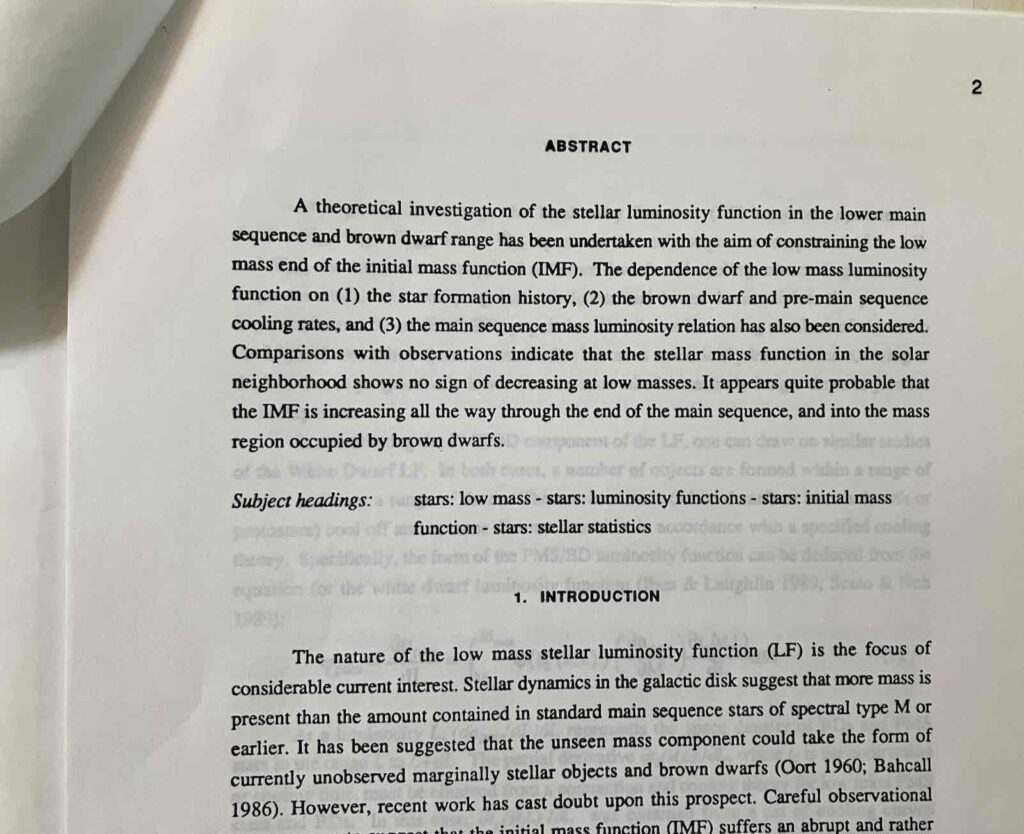

After several weeks, I had an answer. Even if the number of brown dwarfs per unit mass were increasing as one considered lower and lower masses, they would not be expected to show up in the extant surveys! I scrambled to write up a single-author paper. Peter Bodenheimer agreed that it was good enough to submit to the Astrophysical Journal Letters. It seemed to be the real deal.

I remember putting the final version in a mailing envelope and walking it to the post office. That was quite a feeling.

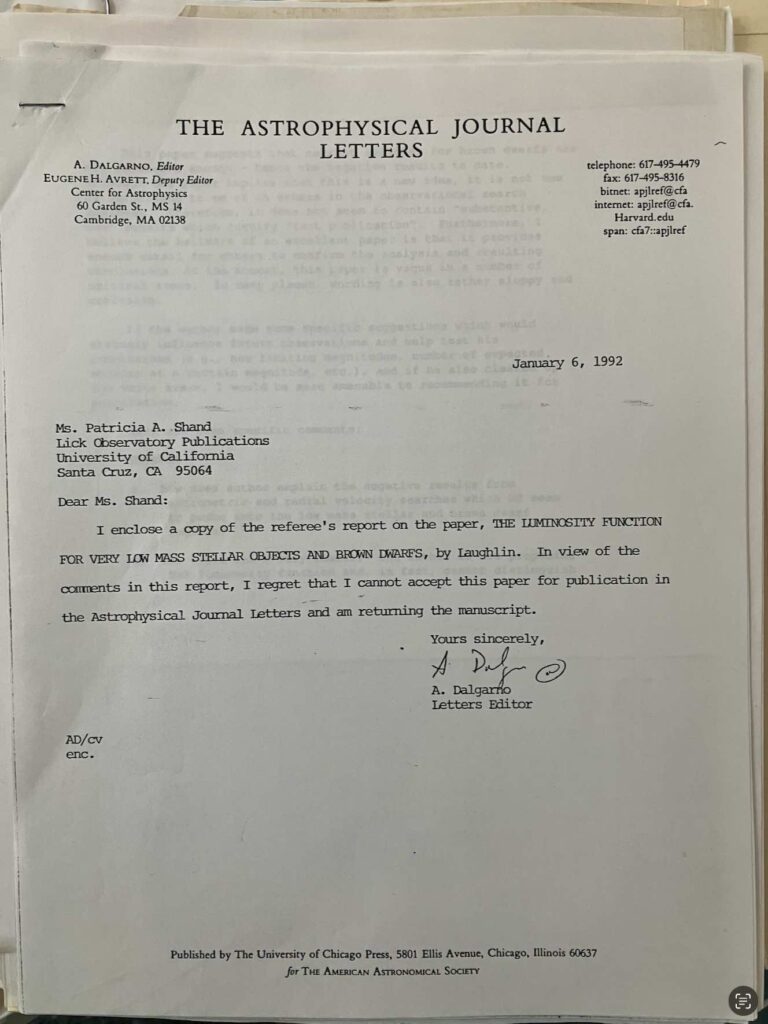

Almost three months went by. In January, one morning, the Observatory Director had placed a letter from Astrophysical Journal Letters in my mailbox. Heart pounding, I quickly opened the envelope.

The yellowing letter and the accompanying referee’s report still carry the dull remnant shock of rejection… “how does author explain the negative results from astrometric and radial velocity searches which DO seem to probe into the low mass stellar and brown dwarf regions?”, “wording is also rather sloppy and confusing”, “the title isn’t very useful” … and on and on.

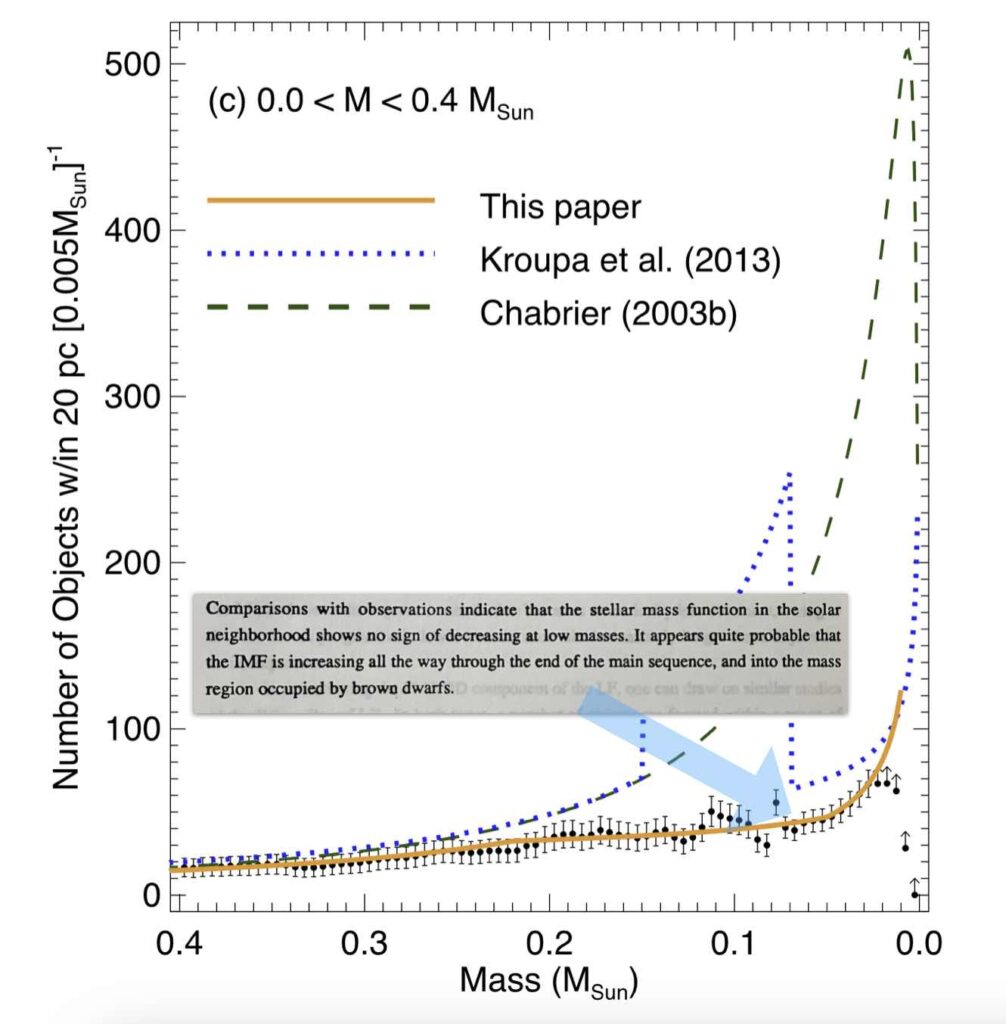

But the brown dwarfs are no longer so elusive. Thousands are known. I Iooked into the literature to see whatever happened to the mass function at the low-mass end. The most definitive treatment seems to be this article by Kirkpatrick et al. from last year:

And satisfyingly: