On October, 29th, 1991, the Galileo probe, flying through the Main Belt on its way to Jupiter, approached within 990 miles of 951 Gaspra and radioed back the first up-close view of an asteroid — a tiny world too small to be round. I was in graduate school at UCSC at the time. At the beginning of November, a glossy black and white clay-coated photograph showing the view above was tacked to the Departmental Bulletin Board. It had been sent direct from JPL in appreciation of Arnold Klemola’s work on the stellar ephemerides that had permitted the flawless navigation of the close approach. The Mosaic Browser hadn’t yet appeared. I remember staring at the physical photograph for a long time.

When a new type of celestial object is first seen in detail, surprises usually result. Gaspra, however, seemed to conform to the popular impression of what an asteroid should look like. I remember thinking how the depiction of the near-Earth asteroid Adonis in Herge’s Explorers on the Moon (1952) had wound up being rather on-the-mark.

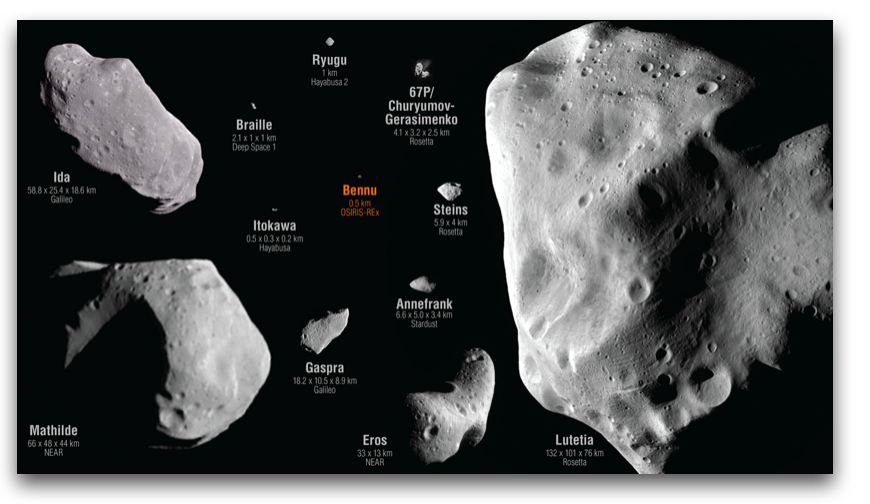

Over the past three-plus decades, spacecraft have visited a whole raft of additional asteroids. The album of returned photographs is a classic of scale invariance in that the images of the asteroids offer almost no clue to their true sizes. It’s a little jarring to see them arranged with their accurate relative sizes, where 14,000 Bennus make a Gaspra and 600 Gaspras comprise a Lutetia.

Uncertainties regarding the true sizes of asteroids would thus seem like a less than front-burner concern. The exact size of this or that particular body would be of enormous interest if it were determined to be on a collision trajectory, but otherwise would presumably be of minor consequence. What you’d think would be a sleepy topic, however, somehow managed to roil into controversy that generated New York Times articles and FOIA requests.