Over a span of months, my late-model Honda Civic accumulated a strata of dust and grime. The situation reached the point where some wag had literally finger-traced “wash me” on the rear window.

I deposited numerous quarters into a machine and eased the manual-drive car into the maw of the automatic wash that is attached to the Chevron on the corner of Los Gatos Boulevard and Blossom Hill Road. Muffled conks and heaves outside the rolled-up windows indicated that the machine’s cycle was about to start. Inside the aging car, it was stuffy, dim, and claustrophobic. Reminiscent, perhaps, of the atmosphere within a sketchily-qualified deep-water submersible while one is still sitting on the deck.

My cell phone rang. A graduate student was on the line. His voice was shaky and panicky, “The server with the Keck vels is exposed to the open Internet!”

“Oh f*ck!” Dread. Horror. This was nightmare made tangible. “What?! How?”

“I don’t know… I, I just found it. One of the post-docs seems to have screwed up and changed the file permissions. Looks like it happened at 2:07 AM last night.”

My mind raced. “Did you lock them down?” That would be the first thing.

“Yes, yes,” he was saying, “I already did that.” I could hear the clatter of rapid typing. “Right now I’m going through the logs to see if they were accessed…”

A hiss of vapor accompanied the hard rat-tat-tat of a water jet against the side of the car. A shaggy red forest of rubbery suds-soaked strips began to lumber over the hood. Time seemed to stretch out like an elastic band.

By late 2007, internal tensions had led to the schism of the successful California-Carnegie Planet Hunting Team. Following the split, I was recruited to join the UCSC-Carnegie branch, and I was responsible for helping to coordinate the analysis of the Doppler velocity measurements.

Those Doppler points represented more than a decade of nights on telescopes. A large tranche of the early data was from Lick Observatory. I had even obtained a scattering of that data — the result of some runs I’d proudly soloed in the summer and autumn of 2001 on the antiquated Coudé Auxiliary of the Hamilton Spectrograph.

The real trove, however, consisted of velocities derived from the tens of thousands of spectra obtained with the HIRES instrument on the Keck I at the summit of Mauna Kea. The long-term several m/s stability and cadenced quality of those measurements had sparked a solid decade of successes. Gliese 876, Upsilon Andromedae, 55 Cancri. Nobel Prize talk was coming down the grapevine. NASA was valuing Keck nights at $100K a pop. Those were the glory days.

When the California-Carnegie team fractured, there was an urgent question of who was going to get to publish which planets from which stars. Fraught back-and-forth negotiations led to a tense stellar draft, in which the two newly-competing teams successively divvied up the juiciest prospects. We lost the initial toss. The Berkeley Team grabbed HD 7924. It was also the first star on our list. I crossed it off with dejected sigh.

The preparation for the stellar draft had got me thinking about the monetary value of planets, and how to properly apportion that value among the stars. At the going NASA Keck rate, the radial velocity data had a street value of approximately $35M. And now, sitting terrified, trapped in the car wash, I had a vision of a Brinks truck left unlocked and unguarded at 2:07 in the morning, crisp stacks of c-notes piled inside for the taking.

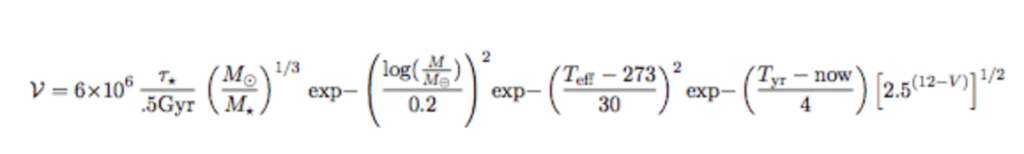

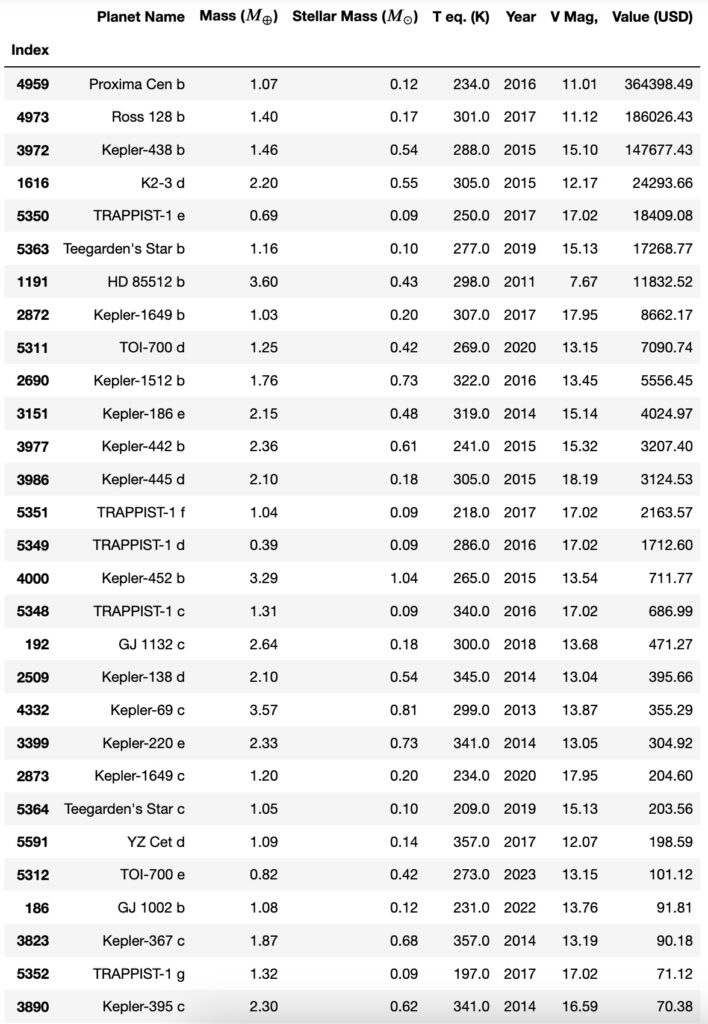

Quote-unquote habitable planets can also be assigned value. Rather than using the cost of Keck nights as the metric, one can use the goal yield of Earth-like worlds and the total cost of the Kepler Mission to establish what society is (or rather was) willing to pay for them. Prior to Kepler’s launch, I proposed the formula:

Where the log is understood to be base-10, now == then == 2009, and V is the parent star’s Johnson V-band magnitude. The expectation was that the Kepler mission would return a cool 700M or so worth of habitable planets.

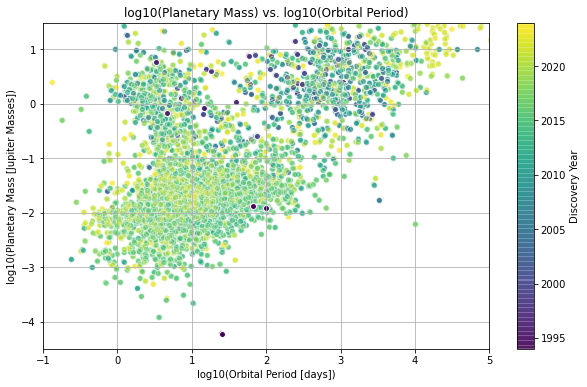

Fifteen years on, it’s interesting to look at how things turned out. Literally thousands of planets have been brought to market. The radical statements from the Geneva Team regarding the absolute profusion of uninhabitable super-Earths with orbital periods ranging from days to weeks have been amply confirmed by the satellite-based photometry.

Yet, despite the impressions one might garner from the various habitable zone galleries, the crop of actual truly-Earth-like prospects, as defined by the valuation formula, is remarkably slim. The discovery efforts vastly under-exceeded expectations in this particular regard. Adopting the fiducial values from the NASA Exoplanet Archive, there are zero million-dollar worlds or even any exoplanets that would require a jumbo mortgage to service. The table just below uses 2010 as the fiducial year.

As expected, Proxima b tops the list by a wide margin. It is interesting, however to see Ross 128b at number 2. This red dwarf host is only 11 light years from Earth, and the relatively subdued fanfare it received is ex-post justification for the stringent time-decay term in the valuation formula. I’ll point out, however, that the artist-impression of Ross 128b is perhaps the best I’ve seen, especially when compared to the janky blue marble efforts that tended to accompany the we-found-a-habitable-planet press releases.

After what seemed like an eternity, the forest of rubber washers trailed off the back of the car. A fine spray heralded the start of the rinse cycle.

“Ahh, OK, OK,” the graduate student said at last, relief permeating his voice, “I’ve gone through the logs. No activity during the span. Nothing. Zero.The vels didn’t leak.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yeah, totally.”

Wash completed, the blue-sky Californial light sparkled off the beads of water still clinging to the car.