An interesting development caught my eye this afternoon. Warm Spitzer, fresh off all that attention generated by the discovery of the TRAPPIST-1 planets — was used by a Michael Gillon-led team to determine that HD 219134 c transits its K-dwarf host star. (Here’s a link to the paper in Nature Astronomy).

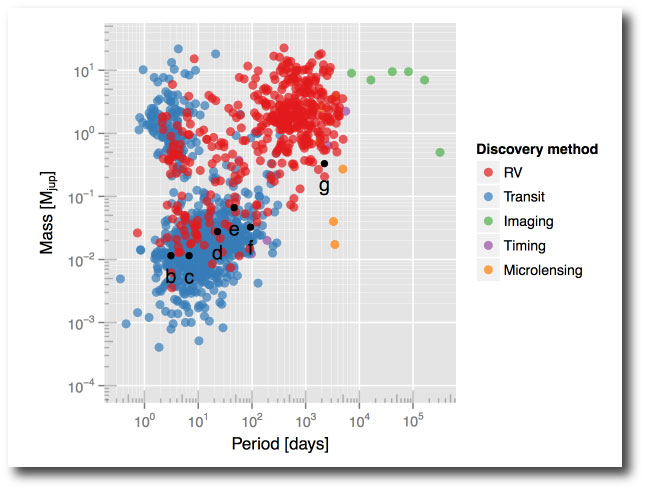

Given the near-constant flux of high-profile exoplanet results, it’s understandable that HD 219134 AKA HR 8832 might not immediately ring a bell. The system is interesting, however, because it is a radial velocity extraction that very cleanly typifies the most common class of systems detected by the Kepler Mission — multiple-transiting collections of super-Earth sized worlds with orbital periods ranging from days to weeks. Upscaled versions, that is, of the Jovian planet-satellite members of our own solar system. The innermost planet in the HD 219134 system is already known to transit. The Gillon et al result adds a second transiting member, which presents itself as the closest transiting extrasolar planet to Earth. Plotting the HD 219134 system on the mass-period diagram emphasizes how effectively it can be viewed as a draw from the Minimum Mass Extrasolar Nebula:

And because of the proximity and the modest radius of the host star, this system will be a fantastic target for future platforms.

Third? Isn’t HD219134 the closest transiting system? Or, were you counting Mercury and Venus? ;)

Third? Isn’t HD219134 the closest known transiting system? Or, were you counting Mercury and Venus.

Sadly, HD219134 is simply too bright for any currently supported JWST observing mode.

Too bright? hmm… post edited.