Yet its presence has been felt, trembling on the far-reaching lines of analysis.

Readers of Systemic certainly need no introduction to what I’m talking about.

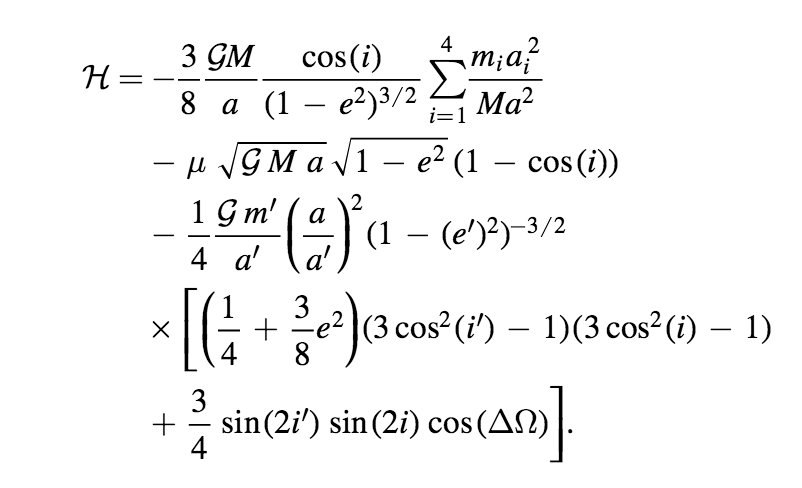

According to the Astronomical Journal’s website, Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown’s paper has been downloaded a staggering 243,547 times in the past five days. To the best of my knowledge, this is perhaps the only time that an autonomous Hamiltonian derived by transferring to a frame co-precessing with the apsidal line of a perturbing object, and then clarified by a canonical change of variables arising from a type-2 generating function, has garnered download numbers that beat out Adele, Justin Bieber, and Flo Rida’s latest figures,

As for the planet itself? A frigid as-yet unseen world with ten times the mass of Earth. Its twenty thousand year orbit is eccentric, and at aphelion it languishes with 500 m/s speed, drifting slowly against the spray of background stars. Its cloud tops glow in the far infrared, a mere 40 Kelvin above absolute zero. At the far point of its orbit, it is invisible to WISE in all its incarnations, and far fainter than the 2MASS limits. Obscure. In the optical, it reflects million-fold diminished rays of the distant Sun to shine in the twenty fourth magnitude. Dim, indeed, but not impossibly dim… Traces of its presence might already reside on the tapes, in the RAID arrays, suspended in the exabyte seas, if one knows just where and how to look.

And there is an undeniable urgency. In England, in 1846, following the announcement of Neptune’s discovery, and with the glory flowing to Urbain J. J. Le Verrier in particular, and to France in general, the Rev. James Challis and the Astronomer Royal George Airy were denounced for their failures in following up John Couch Adams’ predictions.

Adams had done essentially the same work as LeVerrier, but he didn’t push very hard to get his planet detected. The Cambridge astronomers marshaled only vague half-hearted searches, even though they had a substantially longer lead time than the astronomers at the Berlin Observatory who first spotted the planet. “Oh! curse their narcotic Souls!” wrote Adam Sedgwick, professor of geology at Trinity College in reference to Challis and Airy.

So what will it take to find Planet Nine? Mike and Konstantin have started a website that gives details and updates on the search.

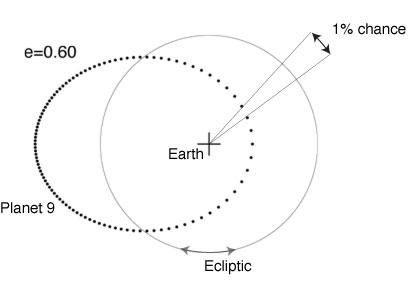

One point that’s interesting to remember is that while an eccentricity, e=0.6 is high, much higher than the rest of the planets in the solar system, it’s not all that high. This planet is no HD 80606b. While it’s true that it tends to congregate near the far point of its orbit, there’s a non-negligible chance of finding it anywhere on its trajectory. In the figure below, the planet is plotted at 100 equal-time increments along its orbit, which shows the distribution of probability for each segment of a great circle that rings the sky:

Similarly, if we assume that its radius is 75% that of Neptune, and that it has a similar albedo, its V magnitude will vary in the following manner during the course of its orbit:

I’ve got a sense — an irresponsible atavistic premonition, actually — that the planet will be caught just as it passes through the 700 AU circle.

We’ve set up a prediction market on the prospects for near-term discovery of Planet Nine at Metaculus. Sign up (or log in) and make your prediction count!

Hi. I have only two questions:

What programme did you use to make those plots?

How did you simulate or create those orbital patterns?

(1) Python/matplotlib + Adobe Illustrator

(2) Here’s my Jupyter notebook (some of the example code on the Planck function and part of the description of Newton’s method was lifted from notes that Mark Krumholz gave me — it’s a new prep for me). I’m teaching an introductory class on scientific computing, so we’re trying to find the planet during class.