This coming July, the planet Neptune will have completed one full orbit since its discovery on September 23, 1846, an event which constituted the occasion, a week ago Sunday in Seattle, for a special session of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society. From the conference program:

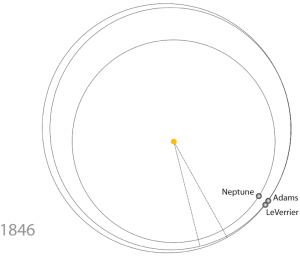

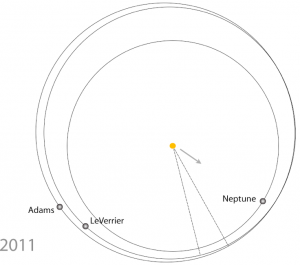

The year 2011 marks not only the 200th anniversary of the French mathematical astronomer Urbain Le Verrier’’s birth, but also the first return of Neptune to its optical-discovery position in 1846. Despite the passage of more than 164 years since that planet discovery, the circumstances surrounding the near-simultaneous mathematical predictions of a transuranian disturbing planet made by Le Verrier and John Couch Adams, a young Fellow in St. John’s College at the University of Cambridge, and the subsequent optical discovery of Neptune by German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory continue to remain controversial. The double anniversary occurring in 2011 is an appropriate time to examine the Neptune discovery event from a number of new perspectives. In this session we shall explore how Cornwall shaped Adams’ early education and his method of locating the presence of a hypothetical disturbing planet. We shall examine the possibility that Adams (and perhaps Le Verrier as well) may have had Asperger’s Syndrome (high-functioning autism), a condition that may explain their difficulties in communicating and interacting with their contemporaries. The intense French press attack on British astronomers immediately after the discovery is examined in detail for the first time. The role that Benjamin Peirce’s analysis of Neptune’s actual orbit (which differed greatly from those hypothesized by Adams and Le Verrier) played in the development and European perception of American astronomy and mathematics will be discussed. We open and close the session with presentations placing the Neptune discovery event within the context of 19th-century science and relating it to modern-day searches for planets in the outskirts of the solar system and around other stars.

That Benjamin Peirce (pictured above), of the Harvard College Observatory, generally plays no role in the Astronomy 101 narrative of the discovery of Neptune is an interesting object lesson in itself: Nobody likes a playa hater. Peirce pointed out the inconvenient truth that the orbits calculated by Adams and LeVerrier, both of whom relied on Bodes’ law to inform their semi-major axes, are startlingly different from the actual orbit of Neptune:

In Peirce’s view, the discovery of Neptune constituted a “happy accident” because the event took place at the fortuitous time when the longitudes of the predicted and observed incarnations of Neptune lay near the same point on the ecliptic. Fast forward by one orbit, and the predictions don’t fare particularly well in a visual search with a 24.4 cm refractor:

Peirce did have a point. If you use a vague empirical law to inform a prediction, are you justified in reaping the accolades? Indeed, some of the praise that came to LeVerrier might justifiably have been seen as over-the-top:

I cannot attempt to convey… the impression that was made on me by the author’s undoubting confidence, but the firmness with which he proclaimed to the observing astronomers, `Look into the place which I have indicated and you will see the planet well.’

–George Bidell Airy, British Astronomer Royal

This scientist, this genius… had discovered a star with the tip of his pen, without other instrument that the strength of his calculations alone.

–Camille Flammarion

Now I’ll be the first to admit, I’m just about the last person who’s justified in taking the high road when it comes to planet “predictions”. For particularly egregious examples of my behavior in this particular regard, one need look no further than here, here or here. Nevertheless, here’s a set of obnoxiously rigorous criteria that I think would have satisfied even Benjamin Peirce’s exacting standards:

In order to be considered as having accurately “predicted” a planet, one must specify, prior to discovery, the planet’s

1. Mean anomaly to within +/- 19 degrees.

2. Argument of periastron to within +/- 19 degrees

3. Orbital eccentricity to within 0.1

4. Period to within 10%

5. Mass to within 10%

6. Inclination to within 10%

7. Longitude of the ascending node to within +/- 19 degrees.

If Ben’s middle name is Franklin, then I think we have found the original “Hawkeye!”

“Choppers!”

Well, I guess he had a good eye.

Talking of planetary discovery controversies, what’s your take on Gliese 581? I’ve had a go at it with the console using the various published datasets and attempted to generate fake datasets to see whether HARPS would have seen the planets in the dataset they used to announce the presence of planet e, as far as I can make out the answer is likely yes…

Pingback: Tweets that mention systemic » Neptune after one orbit -- Topsy.com

But, aren’t all RV planets (not involving a transit), by Le Verrier’s standards, ‘predictions’ rather than ‘discoveries’? All they are is deductions from perturbations to the motion of observable massive bodies. (Of course, the fact that some of them lead to transit detections is a kind of confirmation of all of them, but still…)

Indeed, if you have a candidate traniting planet, and you have done all the BLENDER-type sums to eliminate distant eclipsing binaries etc to x% confidence, but can’t get an RV confirmation, is that a discovery or not?

Pingback: Se l’è presa comoda. | Politica Italiana

@ vagueofgodalming; Kind-of like Kepler-9 d?

With reference to Gliese 581 (and drawing on our Systemic project experience), the controversy will only be settled with the acquisition of more RV data through monitoring of this system. This will improve the planet’s signal and subsequently improve the FAP.

Pingback: Se l’è presa comoda