Mt. Hamilton Main Building at dusk, photo by Laurie Hatch

Last weekend, I wrote a post about the planet — stellar metallicity connection, and the small-scale Doppler-velocity planet search that Debra Fischer and I carried out at Lick Observatory as a precursor to the currently ongoing N2K survey.

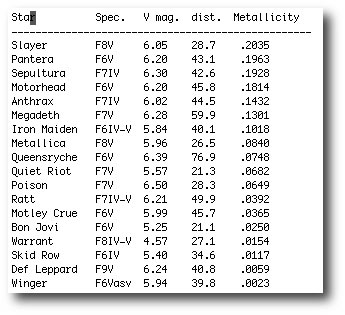

We had eighteen candidate stars on our list, ordered in terms of increasing uvby-determined metallicity, and to keep track of them, we named them after heavy metal bands:

We started observations in September 2000. Several times a month, I would drive up the twisting road to Mt. Hamilton, windows open to the dry chaparral air. At the mountaintop, the observatory buildings on the ridgeline sleep in the hot quiet afternoon sunlight. The scene seems lost in a slower, less hectic time. E-mail, phone messages, deadlines, all-hands division meetings are far away and inconsequential.

After standing and staring for a long time at the sweeping expanse of ridges, mountains and valleys spreading out in all directions, I would pick up a set of keys, a flashlight, a thermous of coffee, and a night lunch from the diner, and walk to the dome.

Once inside, the lost-in-time feeling immediately gives way to the scramble to set up for the night. Open the spectrograph, fill the ccd dewar, focus the optics, set up the iodine cell, obtain the thorium-argon calibration and flat-field images, check the telescope pointing, and run through a number of other ordered tasks, all of which are required for a successful night of observations. We were using the then-undersubscribed 1-meter Coude Auxilliary Telescope, which has a certain Rube-Goldberg aspect to its inner workings. It took all (and more) of my clumsy theorist’s mechanical aptitude to make sure that I didn’t skip a step of the complicated set-up procedure.

Eventually, with the sky grading into deep blue twilight and the night’s first target star acquired, the stress associated with the set-up procedure would dissipate. Because of the small size of the telescope, the individual exposures were long and unhurried. I’d take two and sometimes even three separate half-hour exposures. With the shutter open, with starlight streaming through the iodine cell, reflecting off the spectrograph, and landing on the CCD, there was little to do aside from making sure that the autoguider was doing it’s job of keeping the star centered on the spectrograph entrance slit.

After three months, several of the stars were showing tantalizing hints of short-term radial velocity variablility. All of our main-sequence target stars have “F-type” spectra, meaning that they were somewhat more massive (and thus hotter) than the Sun. It was impossible to get the 3-5 m/s precision that can be obtained with slightly cooler solar-type “G” stars. For F-type stars, the metal lines that greatly aid the measurement of precise Doppler shifts are starting to fade, and, because F-type stars are generally quite young, they are often rapidly rotating. Unless the star is being viewed pole-on (which seems to be bad for planet detectibility) stellar rotation broadens the spectral lines and further degrades the velocity precision.

Mötley Crüe, in particular, was exhibiting radial velocity variations that seemed to strongly imply the presence of a short-period planet. This was mildly surprising, given its rather puny, barely super-solar “80’s hair metal” metallicity of [Fe/H] ~ 0.04 dex. We became more and more excited, as each velocity seemed to come in on target:

I have to go and teach a class now, so I’ll pick up the story sometime during the next few days. Also, when I get back from class, I’ll add the velocities shown in the figure above to the Systemic Console under the name “Mötley Crüe”. If you’re interested, you can then do a quick analysis which will show you why Debra and I were getting excited by the velocities.

“BTW, Does anybody know how to get the umlauts over the o and the u using html?”

Yeah, just write ö for ö and ü for ü. Or just copypaste the letters. Your page is using Unicode, so you can put umlaut letters directly on the webpage without using the HTML code.

PS. Heavy metal bands

I mean, ö and ü.

PS. Heavy metal bands <- spectral metal bands… great pun! ;)

Jyril — Thanks, that works!

Greg